The earth and the other seven planets (in case you didn’t know, Pluto is no longer considered a planet) orbit the sun, which is a very special star. Nevertheless, it is just one of probably more than a septillion (1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) stars in the universe. Each of these stars has a gravitational field, and at least several of them have planets orbiting around them. In other words, each star has its own solar system.

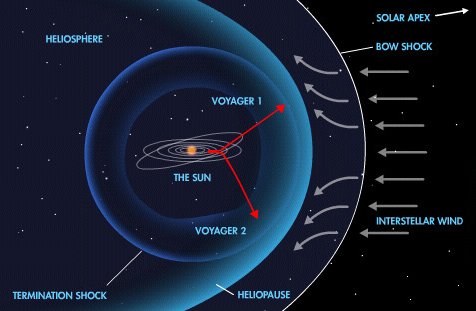

Well, at some point, our solar system has to end and interstellar space (the space between the solar systems of different stars) has to begin. But where, exactly, is that? The robotic spacecraft known as Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are trying to answer that question. They were both launched into space in 1977 (Voyager 2 was launched 16 days earlier than Voyager 1), and they have been traveling away from earth ever since. While they still have fuel, they don’t use it to propel themselves forward. Where they are, the sun’s gravitational field is so weak that they experience essentially no resistance to their travel, so they just keep traveling with the speed their engines gave them long ago. The only thing they use their fuel for is to change orientation, a process called “attitude adjustment.”

Even though Voyager 1 was launched later, it picked up a bit more speed than Voyager 2, so it is farthest away from the earth and the sun. As of the time this article was written, Voyager 1 was more than 18,800,720,000 kilometers (11,682,230,000 miles) from the sun. That’s a long way, but is it far enough to be considered out of our solar system? The surprising answer is that we aren’t really sure!

Most astronomers would say that our solar system is defined by a region in space called the heliosphere, which is a kind of magnetic “bubble” that surrounds the sun. It is produced by cosmic rays that stream from the sun and out into interstellar space. When cosmic rays from interstellar space (often called the “interstellar wind”) collide with the bubble, they are diverted. As a result, few interstellar cosmic rays enter our solar system. The edge of this “bubble” is called the heliopause.

(public domain image)

The obvious way to detect when a spacecraft hits the heliopause, then, is to look at cosmic rays. Solar cosmic rays should decrease dramatically at the heliopause, and interstellar cosmic rays should increase. That happened on August 25, 2012. The solar cosmic ray count dropped quickly, and the interstellar cosmic ray count rose. Eventually, the solar cosmic ray count went to nearly zero.1 That should have been a sure-fire indication that Voyager 1 had left the solar system, right? Well, not exactly.

Since the heliopause is supposed to be the edge of a magnetic bubble, it was thought that the magnetic field detected by the craft should change direction as it passed by. However, it did not. Thus, while the cosmic rays indicated that Voyager 1 had left the solar system, the magnetic field data did not. Most likely, this discrepancy could have been resolved by another instrument on Voyager 1 that detects plasma density, but unfortunately, it stopped working long ago. However, another instrument on board is affected by plasma density, and it gave some readings on April 9, 2013 to indicate that the plasma density is consistent with interstellar space.2 This is a very indirect way of measuring the plasma density, but it was enough confirmation for many scientists. As a result, the consensus is that Voyager 1 did, indeed, leave our solar system back in August of 2012.

Not everyone agrees, however. Heliophysicist Dr. George Gloeckler and his colleague, Dr. Lennard Fisk reject the conclusions of the Voyager team. As Gloeckler says:3

We have not crossed the heliopause.

He sees the magnetic field readings as the key, and they indicate Voyager 1 is still in the heliosphere. An indirect measurement of plasma density is not enough to convince him otherwise, and he also says that he and Fisk can explain all of Voyager 1’s readings without requiring it to be out of the solar system.

Will this argument get resolved? Possibly. Voyager 2’s plasma density instrument is still functional, but it is about 3,400,000,000 kilometers (2,100,000,000 miles) behind Voyager 1. If it can make up the distance without losing the use of its plasma density instrument, it should be able to measure all three relevant pieces of data (cosmic rays, magnetic fields, and plasma density). At that point, the scientists will probably have a better idea of what Voyager 1 experienced when it saw the drop in cosmic rays.

If we get good data from Voyager 2 when it reaches the same distance from the sun, we will probably learn that like most of creation, the edge of our solar system is significantly more complex than we originally thought. Even if we don’t get good data from Voyager 2, the fact is that we have learned an enormous amount from both of the Voyager spacecraft. When you include the fact that we are still learning from them more than 35 years after they were launched, the result is an incredible feat of science and engineering!

REFERENCES

1. W. R. Webber and F. B. McDonald, “Recent Voyager 1 data indicate that on 25 August 2012 at a distance of 121.7 AU from the Sun, sudden and unprecedented intensity changes were observed in anomalous and galactic cosmic rays,” Geophysical Research Letters 40:1665–1668, 2013

Return to Text

2. D. A. Gurnett, W. S Kurth, L. F. Burlaga, and N. F. Ness, “In Situ Observations of Interstellar Plasma with Voyager 1,” Science 341:1489-1492, 2013

Return to Text

3. Richard A. Kerr, “It’s Official – Voyager Has Left the Solar System,” Science 341:1158-1159, 2013

Return to Text

Cool article, Jay. Do you know how long it is until Voyager 2 reaches the August 25, 2012 position of Voyager 1?

Based on its current speed (about 35,000 mph), it will take just about 5.5 years to reach the same distance from the sun that Voyager 1 was at on August 25, 2012. It should still have power by then, so if all the instruments are still working, it should give us a lot more data.

I was trying to visualise these probes as they pass through the vast, cold and emptiness of space. The sheer size and complexity left me feeling humble but almost insignificant in the grand scheme of things, ant-like almost.

Exciting but scary at the same time.