As a result, I was pleased to find that two different readers sent me two different articles about a recent experiment involving dead pig brains. They were both justifiably skeptical of what the articles were saying, and they asked my opinion. I am happy to oblige. The worst of the two articles can be found at Big Think. It is entitled “Yale scientists restore brain function to 32 clinically dead pigs.” It then goes on to say:

The image of an undead brain coming back to live again is the stuff of science fiction…But like any good science fiction, it’s only a matter of time before some manner of it seeps into our reality. This week’s Nature published the findings of researchers who managed to restore function to pigs’ brains that were clinically dead. At least, what we once thought of as dead.

None of this is true. The researchers have accomplished something that overturns the current scientific consensus about the survivability of neurons (the “workhorse” cells of the brain). They also might have developed a technology that will significantly improve drug testing, but they haven’t even come close to restoring brain function!

Not surprisingly, the scientific article that reports on the experiment doesn’t make the kind of outlandish claims you are finding in the popular media. Instead, it lays out precisely what the scientists did: They received about 300 pig heads that were shipped to them on ice from a food processing plant. They surgically removed the brains and put 32 of them in a system called BrainEx, which pumps a mix of chemicals designed to provide oxygen, sugar, and other nutrients to the tissues. The chemical mixture is at normal body temperature, so it essentially performs the functions that blood would perform if the animal were alive. They then studied what happened and compared the results to brains that were not put in the system and brains that were put in a similar system that did not contain the artificial blood.

The brains that were put in the BrainEx system altered the chemical composition of the artificial blood. Once it had left the brains, the chemical mixture was partially depleted of sugar and oxygen. In addition, it contained carbon dioxide that wasn’t originally in the mix. Obviously, this meant some of the cells in the brains were alive – they were taking in the sugar and burning it for energy. When the scientists looked at samples of the brains from the BrainEx system under the microscope, some of the neurons looked healthy, indicating that they were alive during the experiment. They even found that some neurons were able to release neurotransmitters, which is a necessary step in the process that allows one neuron to send signals to another neuron.

This is a major accomplishment, and it does overturn the scientific consensus when it comes to the nature of neurons themselves. These cells have always been considered “fragile,” and it is thought that without a constant supply of blood, neurons die within minutes. That is clearly not true. The pig heads had no blood supply for several hours, yet some of the neurons were still able to perform their basic functions when they were given artificial blood. It also provides the possibility that neurons can be kept alive in the brain after death so that experiments can be performed on them while they are still in the brain. That could helps scientists better understand how drugs that are designed to alter brain function actually work!

However, this did not, in any way, restore function to the brains themselves. Indeed, the artificial blood contained a chemical that specifically reduced the ability of neurons to communicate with one another. That’s what leads to brain function. The reason for this was simple – since the neurons weren’t being regulated the way they are in a living pig, it was thought that the communication would go wild, harming the cells. In addition, the brains were monitored with an EEG throughout the six-hour experiment. During no time did the EEG show anything but a dead brain.

In other words, there was no brain function found in the experiment. Indeed, there was a chemical in the experiment that was designed to stop the process that is necessary for brain function. What if that chemical were removed? Most likely, the fears of the experimenters would have been shown to be correct. Without all the regulatory mechanisms necessary for brain function, individual living neurons would start producing signals like crazy. Those signals contain lots of energy, and that energy would probably kill many of the cells that the artificial blood was sustaining.

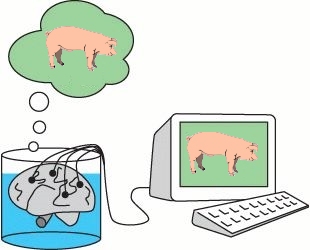

It will be very interesting to see how this technology develops and how it will be used in the future, but if you are hoping for living pig (or other animal) brains in vats, you will be disappointed. The brain is not just a collection of neurons. It is a collection of neurons and support cells whose communication is strictly regulated by a host of different processes. Get rid of those processes, and the brain will cease to function properly. Some cells in the brain might stay alive for a lot longer than we once thought, and some cells can be revived after being “put on ice” for several hours. However, without all the regulatory mechanisms in place, those cells will never form anything close to a functional brain.

The real question is… How close ARE we to RoboCop?

Hehe!

The assumption was, that “Since the neurons weren’t being regulated the way they are in a living pig, it was thought that the communication would go wild, harming the cells,” but they should have experimented with some of the other 268 brains, using artificial blood that didn’t contain the chemical that specifically reduced the ability of neurons to communicate with one another; just to see what would happen, and confirm the “Wild, cell harming communication,” hypothesis

Thank you Dr. Wile. Great job clearing up the hype around this.