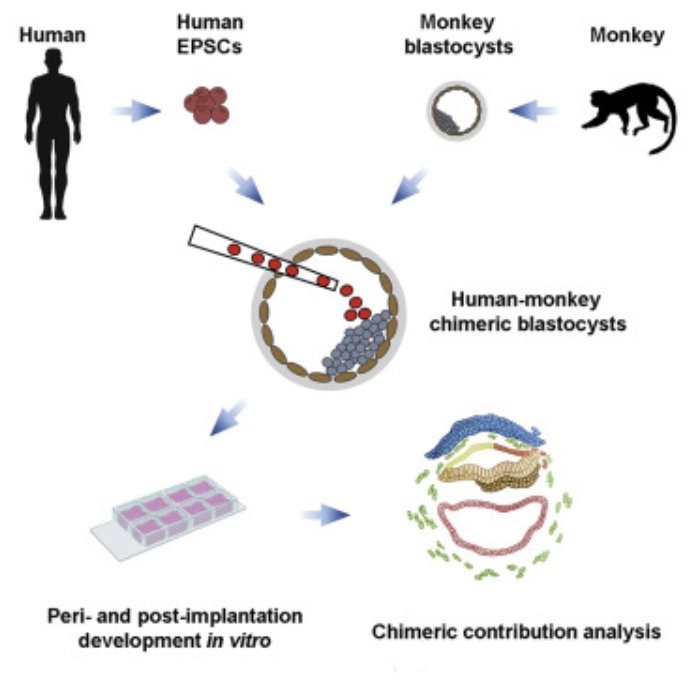

What did the researchers actually do? They first developed a method for fertilizing the eggs of a long-tailed macaque (Macaca fasciularis) so that the monkey embryo could start development in a lab dish instead of the body of a female macaque. Once they accomplished that, they took human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) that had already been developed and injected them into the lab-dish monkey embryos once they reached a specific stage in development, called the “blastocyst stage.” They then followed the development of these mixed embryos over time.

Why would someone want to do something like this? The scientists on the project were mostly interested in trying to understand how the cells in an embryo communicate with one another so that they can do the jobs they need to do to make a baby. They thought that if they could see how the human cells communicated with one another in this kind of system, it would help them understand human embryonic development better. Of course, to “sell” the research, they also indicated that it could help produce animals that could grow human organs for transplant, since many people die waiting for an organ transplant.

Were they successful? Not really, but they were able to get some results. They started with 132 separate monkey embryos, and they injected 25 human stem cells into each of them once they reached the blastocyst stage. Stem cells have the ability to develop into many different kinds of cells, so they hoped that human cells would communicate with one another and mimic what happens during early human embryonic development. However, over the course of 20 days, most of the embryos died. Only three of them survived for 19 days, and there was significant interaction between the human and monkey cells. As a result, it’s not clear how much of what happened to the human cells is related to actual human embryonic development.

Now remember, I said the paper alleviated some of my concerns. That’s because the source of the human cells is not immoral. There are three ways to get human stem cells. The first way is to extract them from a human embryo. This kills the baby, so murders must be committed in order to use such cells. Thus, no one with any sense of morality should be involved in such research. Fortunately, this experiment didn’t use such cells.

The second way to get human stem cells is to harvest them from the umbilical cord after birth or from certain parts of an adult. This doesn’t kill anyone, so there is nothing unethical about their use. Indeed, several successful medical treatments are based on such cells, which are usually called “adult stem cells.” This experiment didn’t use those cells, either. Instead, it used mature cells (from an adult) that had been chemically reprogrammed to act like stem cells. Such cells are usually called “induced pluripotent stem cells,” and once again, no one is killed in the process. Thus, at least the source of human stem cells used in the experiment is a moral one.

However, my concerns are not fully alleviated. After all, this experiment could be done by others who are immoral enough to use stem cells that require babies to be murdered. Indeed, there are probably scientists reading this very paper thinking that one reason the survival rate was so low was because the stem cells did not come from a human embryo. As a result, they might try to replicate this experiment with immorally-sourced stem cells.

Of course, the other serious issue is that this experiment could be altered so that the mixed embryo is implanted back into a female monkey, in hopes that some kind of creature would actually be born. I seriously doubt such a thing could actually happen, because embryonic development is so complex that the communication between monkey and human cells would eventually cause the process to break down. Nevertheless, the possibility exists that such a monster could be produced, which is morally repugnant.

Now I do have to say that the authors of the study went to great pains to make sure that their experiment was deemed “ethical.” However, that doesn’t comfort me in the slightest. After all, the medical community thinks abortion is ethical, and it is clearly not. Given this fact, I don’t think this line of research should be extended. There are just too many ways it could be done immorally, and the medical community has shown that its sense of morality is, at best, stunted.