Evolutionists are fond of stating “facts” that aren’t anywhere near factual. For example, when I was at university, I was taught, as fact, that bacteria evolved the genes needed to resist antibiotics after modern antibiotics were made. As with most evolutionary “facts,” this turned out to be nothing more than wishful thinking on the part of evolutionists. We now know that the genes needed for antibiotic resistance existed in the Middle Ages and back when mammoths roamed the earth. They have even been found in bacteria that have never been exposed to animals, much less any human-made materials.

Of course, being shown to be dead wrong doesn’t produce any caution among evolutionists when it comes to proclaiming the “evidence” for evolution. When Dr. Richard Lenski’s Long Term Evolution Experiment (LTEE) produced bacteria that could digest a chemical called “citrate” in the presence of oxygen, it was hailed as definitive “proof” (a word no scientist should ever use) that unique genes can evolve as a result of random mutation and selection. Once again, that “fact” was demonstrated to be wrong in a series of experiments done by intelligent design advocates. They showed that this was actually the result of an adaptive mutation, which is probably a part of the bacterial genome’s design.

Recently, I learned about an impressive genetic study by young-earth creationists Sal Cordova and Dr. John Sanford. It lays waste to another evolutionary “fact” I was taught at university: the recent evolution of nylon-digesting bacteria. The story goes something like this: In 1975, Japanese researchers found some bacteria, which are now charmingly named Arthrobacteria KI72, living in a pond where the waste from a nylon-producing factory was dumped. The researchers found that this strain of bacteria could digest nylon. Well, nylon wasn’t invented until 1935, and there would be no reason whatsoever for a bacterium to be able to digest nylon before it was invented. Thus, in a mere 40 years, a new gene had evolved, allowing the bacteria to digest something they otherwise could not digest.

Of course, we now know that this story isn’t anywhere close to being true.

First, a couple of minor points. In their landmark study, the Japanese researchers specifically state that the bacteria were isolated from the soil, not a pond. So the common version of this evolutionary myth can’t even get the origin of the bacteria correct. Second, the bacteria were not capable of digesting nylon. They were capable of digesting nylon waste products. As Cordova and Sanford point out in their paper, nylon is made of long molecules that enzymes aren’t typically able to break down. In order for the enzymes to work, the molecules must be much shorter than nylon molecules. So Arthrobacteria KI72 bacteria don’t digest nylon. They digest broken-down bits of nylon molecules. Such sloppy scholarship is typical of evolutionary evangelists, but that’s not the problem with the myth. The problem is that the ability to digest nylon waste products is incredibly common in bacteria from a diverse set of environments.

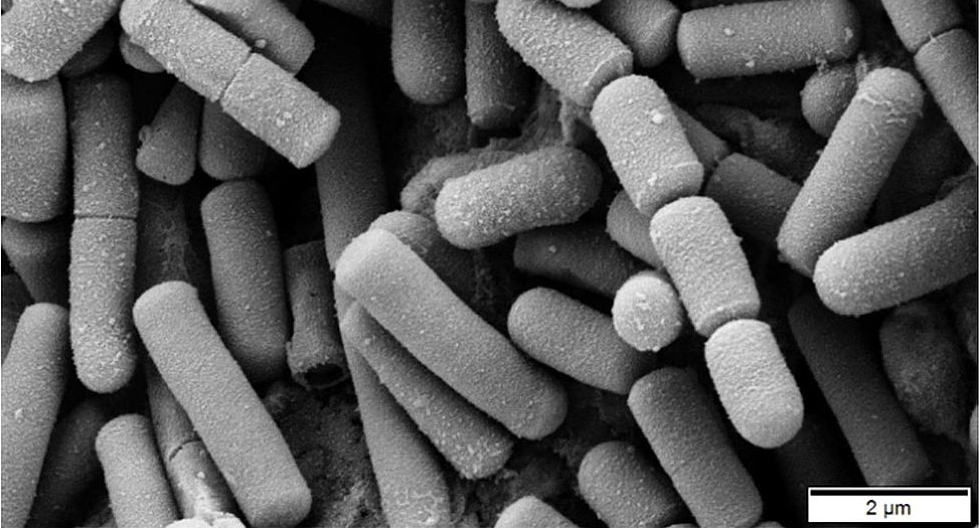

Since Arthrobacteria KI72’s ability to digest nylon waste products was discovered, lots of other bacteria that can do the same thing have also been discovered. For example, the marine bacterium pictured above, Bacillus cereus, has been shown to be able to digest nylon waste products. Two other marine species, Vibrio furnisii and Brevundimonas vesicularis, can do the same thing. Anoxybacillus rupiensis, a bacterium that lives in hot soils in Iraq, has also been shown to be able to digest nylon waste products.

Cordova and Sanford wanted to see if they could find out just how common the ability to digest nylon waste products is among bacteria, so they looked at the NCBI database, which contains genetic data on many species of bacteria. They searched for genes that are similar to the known nylon-waste-digesting genes, commonly called “nylonase genes.” The similarity had to be strong enough to indicate that those genes would allow the bacterium to digest nylon waste products. They found a total of 355 different bacterial species that had such genes! The bacteria come from diverse environments, including one (Cryobacterium arcticum) that lives in arctic soils, far removed from human activity. As the authors state:

Our analyses indicate that nylonase genes are abundant, come in many diverse forms, are found in a great number of organisms, and these organisms are found within a great number of natural environments.

Now remember what the evolutionary myth about nylon-waste-digesting bacteria says. It says that such genes evolved only after 1935. Do you really think that genes which evolved so recently would spread to at least 355 different species of bacteria in “a great number of natural environments” in under 80 years? That’s awfully hard to believe.

Of course, fervent evolutionists regularly believe things that stretch the limits of credulity, so let’s say that this kind of rapid gene dispersal is possible. Cordova and Sanford’s study still invalidates the myth, because the crux of the myth is that there is no reason whatsoever for a bacterium to have a gene that allows it to digest nylon waste products if nylon waste products aren’t around to be digested. However, there aren’t nylon waste products in the vast majority of environments in which these nylon-waste-digesting bacteria are found. Thus, we know for certain that bacteria do, indeed, carry around the gene for nylon-waste digestion, even when there is no nylon waste to digest.

That’s not the end of Cordova and Sanford’s work. They use another biological tool, UNIPROT, which gathers information on proteins that are produced by organisms in nature. They found that there are 1,800 different organisms that produce enzymes which should be able to digest nylon waste products, based on standard biochemical calculations. In other words, the ability to digest nylon waste products seems to be all over creation. They end their paper by analyzing the two competing models for how evolutionists thought nylonase genes evolved. They show that neither model works based on our current knowledge of genetics.

While the last part of the study is interesting, evolutionists can always come up with another model that contains even more wishful thinking. Regardless of the model employed, the ubiquity of nylonase genes and nylon-waste-digesting enzymes show that nylonase genes did not evolve in response to the production of nylon.

Hello Dr.Jay! How are you today? I liked your recent article. I says to us that some “new” traits found in an organism isn’t so new at all, and the best thing to do is search better and(try) not to be biased. (Even though I think EVERYBODY has bias)

God Enlighten you all!

Rationes seminales! The unfolding potentialities of “intelligent seeds” at their given time.

Beautiful concept for reconciling the idea that all life was created in the beginning but also that all life is capable of change.

Thanks for the great post… These digestors come up often in NeoDarwinian apologetics… Which reminds me I need to finish my “Little Locksmiths” analogy. : )

What’s the correct scientific term to use when discussing subjects like this? Do we say it evolved, selected, or adapted to it’s environment in order to eat nylon? This might be a little off-topic, but how much of science should we be skeptical of? For example, the gold origin story goes that a star exploded… and bam, gold! The general scientific consensus is that everything comes from an exploding star. People claim that humans are made out of star dust. Is there any way to prove or disprove that?

I don’t think we know the “correct” scientific term for this process, because we don’t really know what happened. When we didn’t know anything, people said the bacteria “evolved” the ability to eat nylon. Generally, the word “evolve” is inserted anywhere evolutionists don’t know what happened. Now that we know the genes for nylon digestion aren’t novel, we could say that the bacteria with those genes were simply “selected” when nylon was present in abundance. We could also posit that the original genes weren’t very efficient at digesting nylon, because they were being used to digest other things that are similar. Then, when nylon became present, some mutations in some bacteria (perhaps random, perhaps adaptive) occurred, and selection preserved the genes that were more efficient for those bacteria. If that was the case, then adaptation might be a better word. The point is, we don’t know. All we know for sure is that, unlike evolutionists originally hoped, the genes aren’t novel.

We should be skeptical of all science. As Noble Laureate Dr. George Wald said, “Science goes from question to question; big questions, and little, tentative answers. The questions as they age grow ever broader, the answers are seen to be more limited.” This is why science cannot prove anything. Science is very, very tentative in all its conclusion. So the proper question isn’t, “Can you prove it.” That question can be asked only of mathematicians and philosophers. The proper question is, “Is there evidence to support it.” For the nonsense that humans are made of stardust, there is very little evidence for it and a lot of evidence against it.

Will you do a humans / stardust post! Seems like it’s one that’s cropping up on social media again.

I will think about it. It’s just hard to approach nonsense from a scientific point of view.

I’m with John D. I’d like to read a response against the idea (it doesn’t have to be an entire article). According to Space.com, they found molecules that’s essential for life in the Milky Way galaxy…basically the building blocks for life: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur, all have been found in huge sample of stars.

It’s common to claim that the “basic building blocks of life” have been found, but that’s just not true. Carbon, hydrogen, etc. are not the basic building blocks of life. They are the basic building blocks of organic molecules, many of which have nothing to do with life at all. Proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids are the basic building blocks of life, and with the exception of a very simple carbohydrate (glycolaldehyde), none of them have been found in space.

I think the main problem with the humans-stardust idea (from a scientific point of view) is that it is based on selective evidence. Of course there are particles in space that are also found in human bodies (the Periodic Table of Elements is universal, after all). And elements from space may enter earth’s atmosphere and be consumed by us… But, where have we seen DNA get produced from the elements in a star? There is simply not a known way for stardust to turn into a living cell.