In a previous post, I discussed alternative splicing, an amazing aspect of our DNA that allows it to store information in a compact, elegant way. In brief, a gene is actually a recipe that the cell uses to make a particular protein. Since most of a cell’s DNA is in the nucleus, the “recipe” stored in that gene must leave the cell’s nucleus in order to be turned into a protein. To do that, the “recipe” is copied by a molecule called messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA then takes the copied “recipe” out of the nucleus to the ribosome, which is where proteins are made.

In eukaryotic cells (the kinds of cells found in plants and animals), however, something very interesting happens before the mRNA leaves the nucleus. Some parts of the mRNA are cut away, and the remaining parts are then stitched back together. The parts of the mRNA that are cut away never leave the nucleus, so they are called introns (they stay IN the nucleus). The remaining parts that are stitched together are called exons (they EXit the nucleus). For a while, geneticists didn’t know the purpose of introns, so in typical evolutionary fashion, many decided that they had no purpose, and introns were lumped into the category of “junk DNA.” Of course, as we have learned more about genetics, we have learned that the evolution-inspired idea of “junk DNA” is, itself, junk, although some evolutionists still cling to it.

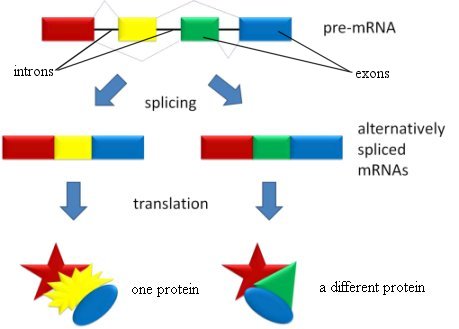

Nowadays, of course, we know the reason that introns exist. It is part of the design of the Creator, allowing DNA to store information in an incredibly efficient way. Each exon represents a “module” of useful information. If the cell stitches the exons together in one way, it makes one protein. If it stitches the exons together in another way, it makes a different protein. As a result, a single gene can actually produce many different proteins. The introns not only serve as a means by which the cell can identify the exons, they also regulate the amount of the various proteins that are being made.

This process of alternative splicing is illustrated in the figure below:

In the previous post about alternative splicing, I discussed how recent evidence suggests that up to 95% of the genes in the human genome participate in this process. However, I did not address how many different proteins a single gene can produce using alternative splicing. In some cases, the answer is truly astounding.