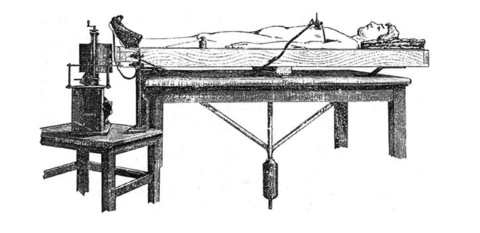

In the 1880s, an Italian scientist named Angelo Mosso built a balance that tried to measure the net flow of blood in the body. A man was put on the balance and asked to clear his mind. The balance was then set so that it stayed horizontal. The man was then asked to read something, and invariably, the balance tilted towards the head, indicating that his brain got heavier. According to Mosso, when the man read a newspaper, the balance would tilt a bit, but when he read a page from a mathematics manual, the balance would tilt more. One man was asked to read a letter from an angry creditor, and it tipped the balance more than anything else!

These results led Mosso to conclude that when the brain is actively working, it gets more blood from the circulatory system. The more it has to work (to process difficult information or strong emotions), the more blood it gets. When I originally read about Mosso’s work years ago, it reminded me of Dr. Duncan MacDougall’s experiments in which he tried to weigh the soul. If you have never heard of Dr. MacDougall’s work, he tried to measure the weight of six terminally-ill patients at the moment they died. He then did the same procedure on dogs. He claimed that while the people lost weight when they died, the dogs did not. As a result, he claimed to have demonstrated that the human soul has weight.

Of course, there are all sorts of problems with Dr. MacDougall’s work, and when I read about Mosso’s work, I rashly put it in the same category. While I am more than willing to believe that the brain needs more nutrients when it is hard at work, I have a hard time believing that its blood flow patterns would be changed dramatically enough to be measured by a balance. Fortunately, other scientists weren’t so rash. Dr. David T. Field and Laura A. Inman decided to replicate Mosso’s experiments, and the results surprised me.

Instead of using a balance that actually tips, Field and Inman used a balance that had a very sensitive scale under the end where the test subject put his or her head. They had fourteen different test subjects, and they adjusted their balance to average out all the changes due to each individual’s breathing, heartbeat, etc. They then had the subject hold his or her breath. It has already been established that holding your breath increases the amount of blood flowing to the brain1 so that the brain can continue to get enough oxygen. Sure enough, when each subject held his or her breath, the scale registered an increase in the weight of the head.

Next, Inman and Field had them either listen to audio or watch a video with audio. When the test subjects listened to audio, the scale measured a small (about a thousandth of a pound) increase in the weight of their heads. When they watched a video with audio, the scale measured a slightly larger increase in the weight of their heads.2 This really does seem to indicate that Mosso was right. When the brain has to work, it gets a larger amount of blood, which results in a slightly heavier brain! When the brain has to work harder (like when it processes audio and video instead of just audio), it gets even heavier!

I am not sure if this finding will revolutionize our understanding of the brain. After all, we have things like fMRI that allows us to measure blood flow in specific regions of the brain, as long as the experiments are set up and analyzed properly. It’s not clear that the kind of bulk measurement done in this experiment will add anything to our knowledge of the brain’s physiology. However, I find it incredibly fascinating that a scientist could measure such tiny changes back in the 1880s. Was his scale really sensitive to very small changes in weight, or was he just unconsciously (or consciously) manipulating the balance to get the result he wanted?

Regardless of the answer to that question, this study has taught me one thing: Don’t dismiss an experimental result because it is old and unexpected!

REFERENCES

1. Palada I, Obad A, Bakovic D, Valic Z, Ivancev V, and Dujic Z., “Cerebral and peripheral hemodynamics and oxygenation during maximal dry breath-holds,” Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 157:374–381, 2007

Return to Text

2. David T. Field and Laura A. Inman, “Weighing brain activity with the balance: a contemporary replication of Angelo Mosso’s historical experiment,” Brain 137(2):634-639, 2014

Return to Text

1)Is this why I have put on weight,Dr Jay?

2)I saw your endorsement of Karen Campbell’s new book. Do you think it’s just for new home educators, or for anyone?

Nice story for you. Last week our ds, who has just turned eleven, numbered the pages of his science notebook. I asked him why he was doing it, and he said that he just wanted to. He was taking pride in his notebook. BTW, he has a thing about Roman numerals, so he used those!

Thanks for telling me about your son taking pride in his notebook, Anthea. That’s great. In answer to your questions:

1) I am actually feeling a little light-headed 😉

2) It is really for anyone. There are several parts in the book where the relationships between parents and their adult children are discussed.

Thanks for the info