Dr. John Charlton Polkinghorne was a theoretical physicist whose work was important enough to earn him election as a fellow in the longest-lived scientific organization in the world, the Royal Society. However, after 25 years of contributing to our knowledge of God’s creation, he decided that his best work in physics was behind him, so he began training to become an Anglican priest. After being ordained, he served in the Anglican Church for 14 years before retiring.

Obviously, Dr. Polkinghorne’s education and life experiences make him an authoritative voice when it comes to the relationship between Christianity and Science. He wrote a lot about the subject, and while I often disagree with him, I have read and appreciated much of what he has written. In 2009, he and one of his students (Nicholas Beale) wrote a book entitled, Questions of Truth: Fifty-one Responses to Questions about God, Science, and Belief. I read it quite a while ago, and I reacted as I usually did – agreeing with some parts of the book and disagreeing with others. However, I was thumbing through it to find a quote I wanted to use, and the Foreword caught my eye. I don’t think I read it when I read the book, so I decided to take a look at it.

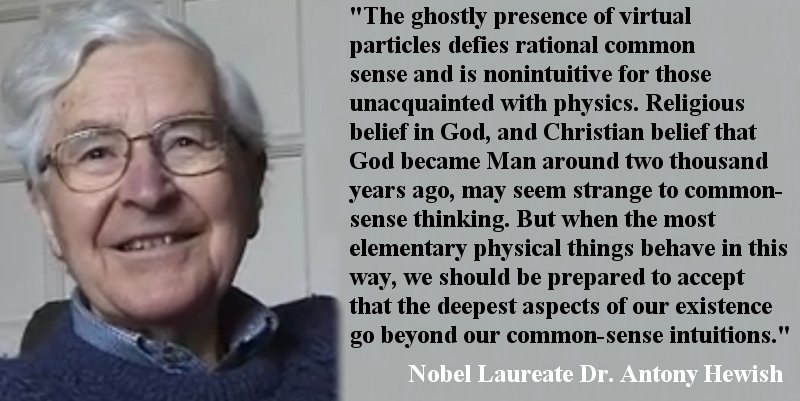

It was written by Nobel Laureate Dr. Antony Hewish, who was an astronomer and a devout Christian. In less than two pages, he makes one of the most interesting arguments I have ever heard regarding the relationship between science and Christianity. He first makes the point, which I make over and over again when I teach science, that science does not follow common-sense thinking. Aristotle used common-sense thinking to come to the conclusion that all objects have a natural state of being at rest, and you have to force them out of that state to get them to move. Galileo and Newton followed experiments rather than common sense, and they demonstrated that an object has no preferred state of motion. It remains in its current state until it is acted on by an outside force. That non-common-sense notion is now called Newton’s First Law of Motion.

Of course, since Dr. Hewish is well-versed in physics, he gives a better example of how physics doesn’t follow common-sense thinking and then makes a conclusion from this fact:

For example, the simplest piece of matter, a hydrogen atom, cannot be accurately described without including the effects caused by the cloud of virtual particles with which it is surrounded. There is no such thing as truly empty space. Quantum theory predicts that even a perfect vacuum is filled with a multitude of particles that flash into and out of existence much too rapidly to be caught by any detector. Yet their existence modifies the motion of electrons orbiting protons in a calculable way that has been verified by direct observation. The ghostly presence of virtual particles defies rational common sense and is nonintuitive for those unacquainted with physics. Religious belief in God, and Christian belief that God became man around two thousand years ago, may seem strange to common-sense thinking. But when the most elementary physical things behave in this way, we should be prepared to accept that the deepest aspects of our existence go beyond our common-sense intuitions.

(John Polkinghorne and Nicholas Bealexii, Questions of Truth: Fifty-one Responses to Questions about God, Science, and Belief, (Presbyterian Publishing 2009), p. xii)

In the end, Dr. Hewish is making the case that understanding modern physics should make you more inclined to be a Christian (or at least more inclined to be religious), since it conditions you to believe that the universe is based on mysterious processes that cannot be directly observed.

I have to say that this has happened in my own life, even though I was not aware of it. I went from being an atheist to believing in some kind of Creator because science showed me that the universe was obviously the result of design. I eventually became a Christian because after reading extensively on world religions, by grace I saw that Christianity is supported by the most evidence. I was initially very uncomfortable with the mysteries that are inherently a part of Christianity, but as I grew older, I became more and more comfortable with them. I thought that this was because I had grown accustomed to them. However, after reading Dr. Hewish’s foreword, I noticed that my level of comfort with the mysteries of Christianity coincided with my increasing knowledge of quantum mechanics.

Dr. Hewish seems to have hit the nail on the head, at least when it comes to how modern physics has helped me grow in my faith.

The bit about virtual particles struck a resonance in my memory of a particularly evocative phrase I remember singing in choir several years back. The phrase is from a Kathleen Raine poem and goes:

Who stands at my door in the storm and rain

On the threshold of being?

One who waits till you call him in

From the empty night.

“On the threshold of being” sounds like an apt description for virtual particles in an electron cloud, or for that matter, the as yet unformed fruit of God’s grace poured out on us.

Common sense in this case is a reference to a shared experience. That experience is that of a macroscopically homogenized concatenation of radically divergent quantum temporal frames of reference (TFR). Matter is only matter in one TFR, but energy in another. If you jostle it such that you turn it’s TFR, it dramatically affects its local temporal context. We can talk about photons from our TFR, but in another TFR, we find that it’s actually the source particle in a process of temporal and spatial dilation transferring energy to what seems to us to be a distant particle. That’s why we get a kind of a wave and an interference pattern in the homogenized temporal context.

The question is: What is the fundamental basis for all of this? What is the ethereal constant? It’s not space or time as we might think since those things are affected by matter. It’s not matter or energy since that’s affected by time and space. None of those things provides an adequate foundation for the others. We have the answer in Scripture. There is a Creator who not only creates but sustains. How he does this cannot be discoverable. The physical world isn’t arbitrary but has a design down to the quantum parts that we can only theorize. This Creator has purpose and intention, and we would do well to listen to what he has to say to us.

That kind of reminds me of that saying by Richard Feynman: “I would rather have questions that can’t be answered that answers that can’t be questioned.” I would say, however, that one definition of science is the discipline of discovering how God creates and sustains. It’s true, we probably won’t discover in this life exactly how he does it all, and we definitely won’t discover in this life all of how he does it, but He has given us a great deal that we are able to discover. As it says in Proverbs “It is the glory of God to conceal a matter and the glory of kings to search it out.”