Many whales have an intricate method of communication that allows them to be highly social. Most social mammals rely on visual cues for communication, but because the water they live in inhibits the effectiveness of visual cues, whales mostly communicate with vocalizations. Dolphins, for example communicate with clicks, whistles, and other sounds. A few years ago, researchers learned that dolphins use their whistles to identify other dolphins by name. Two dolphins that are “talking” might even refer to a third dolphin by name as a part of their “conversation”!2

Well, it seems there is another thing to add to the ever-growing list of what makes whales so amazing: they also have great poop!

To understand why whale poop is so great, you have to understand how important nitrogen is to the algae and other photosynthetic creatures that form the base of the food web in the ocean. Nitrogen is an important element in the formation of amino acids, which are the constituents of proteins. Thus, for photosynthetic creatures to produce the proteins they need to live, they must have an ample supply of nitrogen.

Now there is plenty of nitrogen in the air. Indeed, 78% of dry air is composed of nitrogen gas.3 However, nitrogen gas is not very reactive, so it cannot be incorporated into the biochemistry of most photosynthetic organisms. As a result, they must get nitrogen in a more chemically reactive form. Typically, nitrates or ammonium ions do the trick.

So where do these more reactive forms of nitrogen come from? There are many sources, and one of the most important is the various rivers that dump water and sediments into the ocean. The water and sediments are typically rich in nitrates and ammonium ions. In addition, the nitrogen contained in waste products such as urine and feces can be recycled back into the ocean as well, but there is a bit of a problem with that.

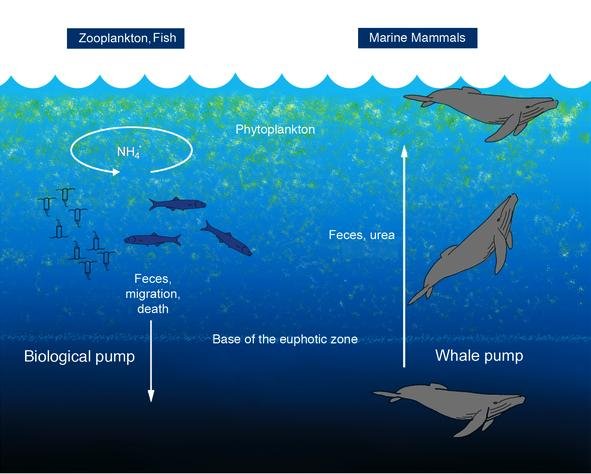

Dead animals and feces tend to sink. Even urine can be a problem, as fish tend to urinate at depth, and the photosynthetic organisms tend to be near the surface. Thus, there needs to be some way to get much-needed nitrogen from deep in the ocean to somewhere near the surface. There are currents and “upwelling” events in the ocean that help to do this, but it turns out that marine mammals, especially whales and seals, do it continually!

Joe Roman and James J. McCarthy have a study in PLoS One4 that looked at what happens when whales poop. Unlike the feces of most mammals, whale poop is thin and buoyant. Thus, it tends to float. Also, since marine mammals spend a lot of time near the surface breathing, they mostly poop near the surface. Well, their poop is laden with nitrogen, so their poop actually replenishes nitrogen near the surface! It turns out that in Roman and McCarthy’s study (which covered the Gulf of Maine), the amount of nitrogen the whales added to the waters near the surface of the ocean was greater than the amount of nitrogen supplied to the Gulf of Maine by all the rivers that flow into it!

This is a particularly neat effect, because many whales tend to feed at depth. Thus, they consume nitrogen (in the form of ocean animals) from deep in the ocean, and then they move up to the surface and replenish the nitrogen there. This is opposite of what happens in many other cases in the ocean, where fish and other ocean animals feed on the photosynthetic organisms and then release wastes deeper in the ocean and sink when they die.

Indeed, Roman and McCarthy call the process they studied the “whale pump,” and they say it helps to balance out the effect of the “biological pump,” which tends to take nitrogen from the surface of the ocean and transfer it to the ocean depths. Here is how they illustrate the two competing processes:

In addition to what this research adds to our knowledge of how nitrogen is recycled in creation, it tells me two things. First, it tells me that if you want to have a healthy ocean with lots of fishes, you need whales. Thus, unlike some have argued, whales are not a detriment to commercial fishing. They are actually a boon. If you increase whale populations using good conservation methods, you will increase the base of the ocean’s food web. Long term, that means you will have more fish to catch and sell.

The other thing this research does is add to the growing list of things that show this world and everything in it have been designed. If you aren’t willing to follow the evidence and admit to the fact that the natural world is the result of an intelligent designer, you are forced to believe that this elegant, efficient nitrogen “pump” is just a lucky byproduct of some unguided evolutionary process. You must believe that this process, which focuses on the survival ability of the whales, just happened to also produce a pump that supports the health of the entire ocean ecosystem. I just don’t have enough faith to believe in that kind of luck!

REFERENCES

1. Anne Hildyard, Endangered Wildlife and Plants of the World, Vol. 12, Marshall Cavendish, 2001, p. 1646

Return to Text

2. Janik, V.M., Sayigh, L.S. and Wells, R.S., “Signature whistle shape conveys identity information to bottlenose dolphins,” Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 103:8293-8297,2006

Return to Text

3. James D. Mauseth, Botany: An Introduction to Plant Biology, Fourth Edition, Jones & Bartlett, 2008, p. 156

Return to Text

4. Joe Roman and James J. McCarthy, “The Whale Pump: Marine Mammals Enhance Primary Productivity in a Coastal Basin,” Plos ONE, 5(10): e13255. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013255, 2010 (Available online)

Return to Text

If my Darwinian timeline is correct, you need millions of years to get fish onto land in the first place, then they have to go through dinosaurs, birds, mammals, back into the sea, and develop puffed up poop. So for the theory to work there must be/have been some other factor that did the same job for those huge expanses of time. Is there?

Josiah, I had not thought about that at all. It is an interesting point, but I think there are too many unknowns. After all, we didn’t even know about the “whale pump” until recently. Who knows what else we are missing?

Since I don’t think we have fossilized remains of extinct marine reptile poop (certainly not of all known genera), I guess you could assume that the large marine reptiles did this job until they went extinct. You might also postulate that there was more nitrogen in the sediments that washed into the ocean, since many ecological niches on land were not exploited in the early stages of land vertebrate evolution.

In the end, I think there are probably scenarios that evolutionists could use to get rid of the timing problem. But even those scenarios still depend on a lot of luck. Of course, evolutionists are used to putting their faith in luck, so that probably isn’t a problem for them.

I’d love to know the keyword search you used to find this research information :).

Indeed we can truly say:

“Let heaven and earth praise him,

the seas and all that move in them” Ps. 69:34

I thought you might be interested in this one, Sherri. I wish I could be that lucky on keyword searches! I actually read PLoS ONE regularly (along with Science, Science News, and Chemical and Engineering News). There are others I read infrequently (such as Nature and the YE peer-reviewed journals), but with those four journals, I get a pretty good view of what’s going on in science.

Good timing! We were just today reading about the nitrogen cycle in Apologia’s Marine Biology book and this is a great extra.

Kathy, here’s more good timing. The “Sherri Seligson” who also commented on this post is the author of that awesome book!

🙂