Mark Armitage is doing some of today’s most exciting research on fossils (see here, here, here, here, and here). He recently presented some of his research at the 2023 Microscopy and Microanalysis annual meeting, which published its proceedings.

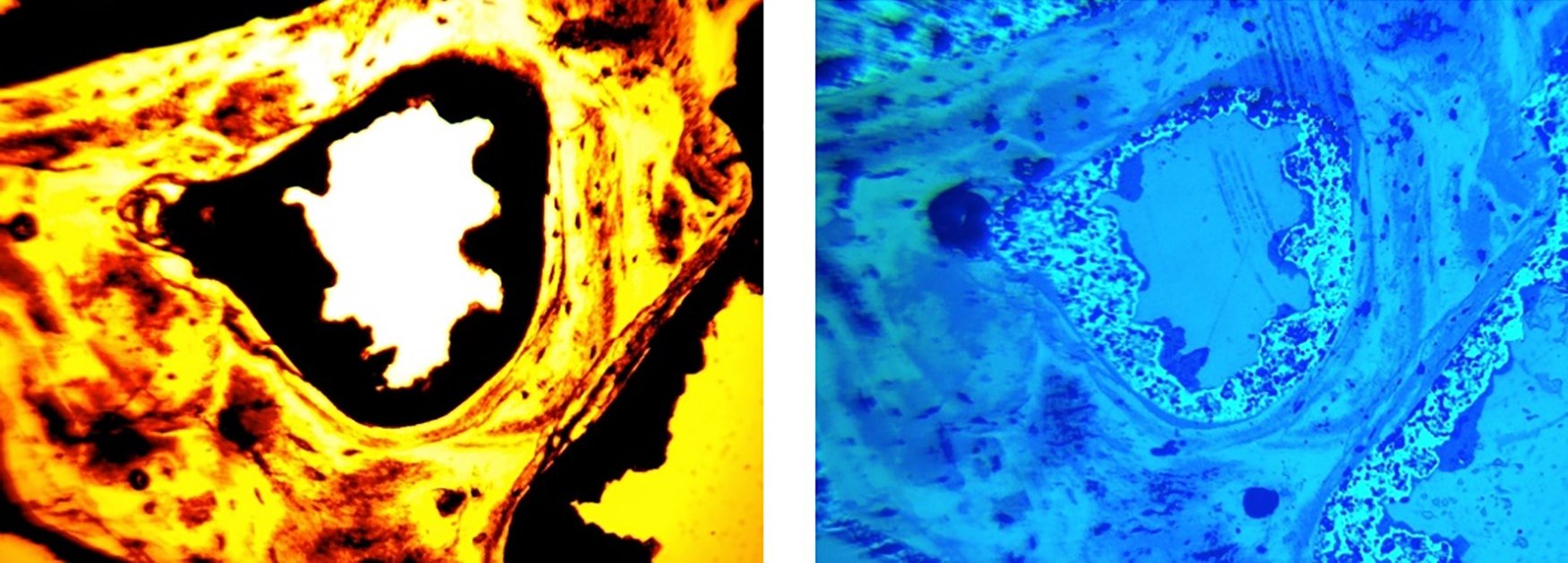

To my mind, there are three important takeaways from the presentation. First, he finds blood clots in fossils that are much older that what has been commonly reported. Most of these reports are about fossils that are supposed to be 65-70 million years old. Some of the fossils he reports on here are supposed to be 270-300 million years old! That’s what the illustration at the top of this article shows. On the left is a standard microscope image of an early Permian amphibian fossil. The yellow material is bone, and the image is centered on a canal that runs through the bone. When the specimen was alive, the canal held blood vessels and nerves. The white area is empty, and the dark material between the empty space and the bone tissue is clotted blood. On the right, you see what happens when that same sample is hit with ultraviolet light. The dark splotches you see come from iron in the blood clot. When hit with ultraviolet light, iron emits light of a specific wavelength, and that’s the wavelength emitted here. Thus, we know this is iron, and since it is in the clot, it is iron from the animal’s blood. If you want to believe the old-earth timescale, then, you have to believe that a blood clot is able to exist for 270-300 million years without rotting away!

That brings me to the second important takeaway. In a desperate attempt to explain how soft tissue can be in fossils that are supposed to be millions of years old, Schweitzer and her colleagues published a paper suggesting that iron is the key to this remarkable preservation. In that paper, they show how iron from blood can reduce the degradation of blood vessels over a period of two years. However, the experiment required that the blood be treated with an anticoagulant. That way, iron could diffuse throughout the tissue that was being preserved. Armitage’s results show that’s not realistic. Instead, the blood clots trap the iron so that it is not available to the rest of the tissue. This adds to the other arguments which indicate that Schweitzer’s iron-preservation hypothesis is not valid.

The last very important takeaway is how these results affect research that has already been done. As Armitage’s paper says:

We also note that many histological dinosaur bone studies reveal unreported clots, thus we encourage workers to examine their sections for iron auto-fluorescence response under UVFL.

In other words, because of Armitage’s work, we can look at past images that have already been published and see that there are blood clots in previously-described fossils that were not recognized by the researchers who published the studies. Thus, paleontologists have the opportunity to learn more from the fossils that they have already examined. I truly hope that at least some of those scientists are curious enough to take Armitage’s suggestion!

Thank you for sharing these exciting research findings as many of us are not able to keep up with these scientific presentations.