I saw this Science Alert article come across my Facebook feed a few days ago, and I read it with interest. Written by two researchers from the University of Maryland, it makes some pretty strong statements about the effectiveness of reading a digital article compared to a print article. Essentially, the researchers say that for specific kinds of articles, students’ comprehension is better if the article is read in print form as opposed to digital form. They make this statement based on a review of the studies that already exist as well a study they published two years ago. While I think they are probably correct in their assessment, I am struck by how small the difference really is.

For the purpose of this article, I will concentrate on their new study. In their Science Alert article, they refer to it as three studies, but it is published as a single paper. In the study, they had 90 undergraduate students who were enrolled in human development and educational psychology courses read a total of four articles: two digital and two in print. Two of them were newspaper articles and two were excerpts from books. They were all roughly the same length (about 450 words). They dealt with childhood Autsim, ADHD, Asthma, and Allergies. Presumably, all of those topics would be of interest to the students, given the classes in which they were enrolled.

Before they did any reading, the students were asked to assess themselves on their knowledge of the four topics about which they would be reading. They were also asked which medium they preferred to read: digital or print. They were also asked about how frequently they used each medium. They were then asked to read the articles, but the order in which the articles were read changed from student to student. Some would switch between digital and print, while others would read the first two in one medium and then the second two in the other medium. That way, any effect from switching between the media would not be very strong.

After each reading, students were asked to identify three things: the main idea of the article, its key points, and any other relevant information that they remembered from the article. The researchers had asked the authors of the articles these same questions as well as two independent readers. Those were considered the correct answers. Two trained graders independently compared the students’ answers to the correct answers, and the grades they assigned were in agreement 98.5% of the time. For the 1.5% of the time they didn’t agree, they then discussed the grading and came to a mutual agreement.

After all four readings and tests, the students were then asked in which medium they think they performed best. As you will see, that’s probably the most interesting aspect of the study.

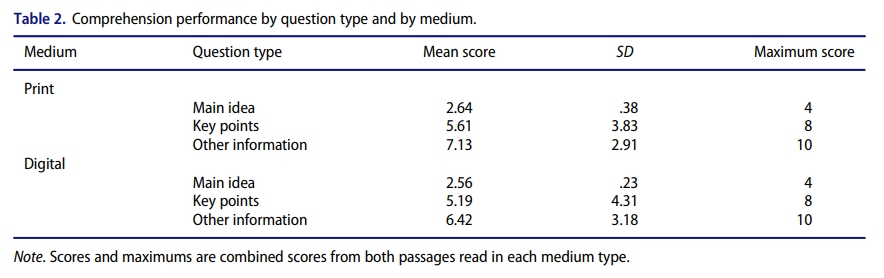

What were the results? Students, on average, preferred the digital medium, but the amount of preference changed depending on the situation. Students heavily favored the digital platform for newspaper and academic reading. They also preferred the digital platform for “fun” reading (like reading on vacation), but not as strongly. What about the students’ comprehension of what they were reading? Here is the table the researchers present in their article:

These are the combined results, averaging all four readings done by each student. The “Mean Score” is the average, while “SD” is the standard deviation, which is a measure of how much variation exists among the subjects. When the standard deviation is low, the subjects scored very similarly. When the standard deviation is high, there are big differences among the subjects’ scores. The “Maximum Score” is what a student would get if he or she answered every question perfectly.

Now here’s the thing you have to understand about comparing people: since each person is different, you expect differences to exist naturally. As a result, if you do a study like this, some of the differences you measure between print and digital will come from the inherent differences among the students, not the differences between the media themselves. Those inherent differences produce what is referred to as statistical error. A nice rule of thumb is that the statistical error depends on the square root of the number of data sets you have. Take the square root of your number of subjects, divide by your number of subjects, and multiply by 100. That will give you a rough estimate of the statistical error in your study.

So, for this study, a rough estimate of the statistical error is the square root of 90, divided by 90, times 100. That’s about 11%. So, if the differences between the scores for digital and print are within 11% of one another, you can’t say they are different. They could very well be the same, and the differences you see could be the result of statistical error. Using this rough estimate, then, you can’t say that any of the differences between digital and print are real. All of the differences in the mean scores could very well be the result of statistical error.

So does that mean that this study doesn’t really say anything about the difference between digital and print? Not exactly. Since all three digital scores are lower than all three print scores, there might be some difference. If the error were truly statistical, you would expect that the digital score might be higher in at least one of the three cases. It is not. So in the end, there probably was less comprehension among the students when they read the digital articles, but the effect was pretty small (less than the statistical error).

Here’s the fascinating part of the study: The students were asked which medium they think gave them the best scores. They weren’t shown their scores. They were just asked what they thought would happen when their digital scores were compared to their print scores. 69% said that they scored better using the digital medium, while only 18% said that they scored better using print. The others thought that the medium didn’t affect their scores. So while the majority of students thought they were comprehending more using the digital medium, they were actually comprehending more using print! That result, more than any other, is the one that stands out to me. Why would students not be able to judge the medium from which they learned best?

In the end, I think this is a good study, but I don’t think the results are definitive. A similar study with a lot more participants might help better pin down the differences between print and digital media. In addition, a similar study should be done using longer articles to see what difference that produces.

An interesting article, and I enjoyed the irony of reading it digitally 🙂

Hehe. You could have printed it out and then read it!

Was going to make the same comment. 😉

I have to add, though, that so far as I am aware, no studies have been done on the e-Ink digital medium, as opposed to a lit display screen, and no studies seem to have considered display resolution (in DPI); could it be that relatively low resolution displays affect things? The difference between 96 DPI and 600 DPI could very well be significant.

Those are good points. I have not seen any studies that address them.

I figure they should be pretty close as long as font and reading conditions were similar.

For myself, I prefer print rather than digital, although I love the immediate access of digital media.

My short-term memory is terrible and I rely on the feel, look, and smell of the book in where the media is placed (thickness in the right and left hand, page color, font, stains on the page, etc) as well as the location on the page for the short-term memory to retain it long enough to make it into long-term memory. Digital media is usually void of unique markings and it makes it harder for me to read. I usually have to go back and read passages twice.

This is indeed interesting. But, uh… my first thought was definitely that the average undergrad isn’t all that bright, and these days is inured to screens – along with the concomitant notion that technology makes everything better. I would hope that students doing educational psychology would be more suspicious of such things, but being not too long out of undergrad I doubt it. So I can’t help but take the result that students assessed themselves as doing better on the digital media to mean they just have a naive perspective of technology, like most people. And that isn’t all that surprising, though it is depressing.

Anyway, I feel like it’s obvious that holding a phone or a laptop puts us in entirely different mindset from that holding a book produces, even aside from the way we conceptualize moving forward in the material. A book is far more jealous of its purpose. I especially can’t imagine preferring reading digital works for leisure.

> “I especially can’t imagine preferring reading digital works for leisure”

I suspect you have not had the pleasure of reading for pleasure on a Kindle. Not that I am an Amazon shill, but I find that reading is greatly enhance on my Kindle; so much so that I eschew printed material, *especially* for pleasure reading.

Oh – hi. No, I haven’t used a Kindle or other E Ink reader.

What just occurred to me is that people need to read. Also, considering the comment about how undergrads are less intelligent: It’s not what you know (or how much) but who you know. The electronic and written word likewise have a source, even indirectly. Lots of information can also be deceptive. The world we live in, the digital age, is a glutton for temporay, fleeting information. It comes and goes, more like a match than even the wind. Somehow the written word reveals permanence, most likely in Christ.

I found this quote in a bookstore window, and I think it applies to this post/study:

“Consider the Internet. Information is not necessarily knowledge. Knowledge is not necessarily comprehension. Comprehension may not yet understand. Understanding is not yet mastery, and mastery is not yet wisdom. Information does not reveal relevant context, just as context may exclude relevant detail.

Consider books. Books cannot be turned off or edited after publication. Books require and provide a context of peace. Books are not the color manipulated programmed propaganda that agitates your retina, mental state and sleep. Books enfold and inspire you. Once bought, they are your own. Books are not bugged to reveal your every interest to anonymous researchers who aim to hypnotically exploit your preferences for profit and your secrets for sinister political purposes. Books are their author’s lives and art. Books are the cultural legacy of the world.

Buy books. They’re a deep resource, a good investment and a great gift.”

-Jakushu Gregory Wood, Forest Books