In one of my online biology classes last week, a student asked if I had any comments on the new organ that was just discovered in the human body. I didn’t have any comments, because I didn’t know anything about it. I expressed a lot of skepticism, saying that with all the imaging techniques available to scientists, it’s hard to imagine that an organ in the human body has been missed. However, I promised the student I would look into it, and while I hesitate to call it a new organ, it turns out that a new feature of the human body has most certainly been discovered!

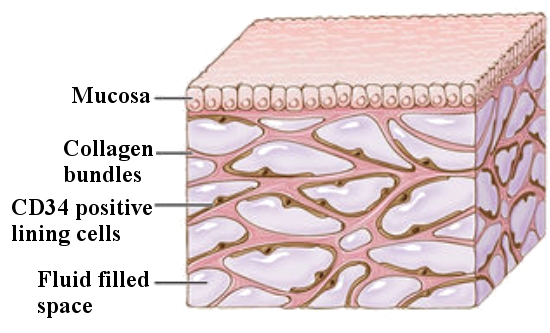

You can read about it in the open-access article published by Scientific Reports. As shown in the illustration above, the researchers found that wherever tissues are stretched or compressed (like the lungs or even the intestines), there is a network of fluid-filled spaces underneath. In the illustration above, think of the part labeled “Mucosa” as the lining of an organ. Underneath that lining, there is a mesh of collagen proteins and elastin proteins (elastin is a part of the “collagen bundle” in the illustration). Those proteins have specific cells attached to them that react to CD34, a stain used to highlight a feature of certain cells when they are viewed under a microscope. In between this mesh of proteins and cells, the spaces are filled with fluid.

For a long time, anatomists have understood that there is a lot of fluid in between the cells of an organism. It is called “interstitial fluid,” and it makes up about 16% of the human body’s weight. It bathes the cells, keeping their environment reasonably constant and serving as way that cells can exchange chemicals with the rest of the body. It comes from the blood, and then it drains into the lymphatic system, where it is cleaned and returned to the blood. So the fluid found in those spaces is not new. The fact that the fluid is found in a mesh of proteins and cells and forms the sponge-like structure illustrated above was completely unknown up to this point.

How did medical scientists miss this for so long? Because the typical way we study tissues microscopically is to cut them into thin strips and then add stains to those strips to highlight the features that we want to study. Specific stains (like CD34) tend to highlight specific features of the tissue, making it easier to see them under the microscope. This process is usually called “fixing” the tissue for microscopic examination, and it destroys the structure.

How did these scientists find what the fixing process destroys? They were using a relatively new technique called “probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy.” Anything with such a long name has to be high-tech, right? Essentially, a camera is put on a cable that can be snaked into the body. That’s an “endoscope,” and it has been around for a long time. The new aspect of this technique is that the camera is equipped with a laser and several sensors designed to detect the light that comes back from the tissue once the laser lights it up. Those sensors send information back to an imaging system, and it produces a microscopic view of the tissues.

So rather than looking at processed tissue in a microscope outside the body, the researchers pushed a high-tech microscope inside the body and looked at the tissues as they exist there. This, of course, gets rid of any effects caused by the fixing process. Initially, the researchers were using the technique to look for cancer in a patient’s bile duct. However, when they saw this structure they couldn’t recognize, they decided to look at other parts of the body (like the entire digestive tract, bladder, skin, and arteries), and they found it there as well! Eventually, they were able to figure out that they could preserve this structure for analysis outside the body if the samples were quickly frozen before they were put through the fixing process.

Why did my student say that this is a new organ? Because the popular science media (like National Geographic and EurekAlert) are calling it that. However, the researchers never call it an organ. Instead, they describe it as:

…a previously unrecognized, though widespread, macroscopic, fluid-filled space within and between tissues, a novel expansion and specification of the concept of the human interstitium.

The term “interstitium” refers to the sum total of all the interstitial fluid in the body. So this isn’t really a new organ. However, it does tell us that, like all of nature, the interstitium is significantly more complex and well-designed than we had previously imagined. Indeed, the researchers also write:

Our findings necessitate reconsideration of many of the normal functional activities of different organs and of disordered fluid dynamics in the setting of disease…

The more we learn about nature, the more it reveals the majesty of its Creator!

Great post, Dr. Jay! I’m always fascinated with a discovery within our body that was, once cryptic. That just show us that the more we know, perhaps, the less we know! God Enlighten you!

Now, I’m curious about the tailbone. Some authors say it is useless; however one of the most reliable websites I ever know, the Mayo Clinic says it’s important to give support to our pelvic floor. And other web site specialized in Spine Health says the same thing, and more. (Though, I don’t know if the second web site is as reliable as the Mayo Clinic)

Do we know weather we discovered something new that may had confirmed the theory of those authors that say the tailbone is useless?

God Enlighten you!

The tailbone is neither useless nor a vestige of evolution. It is an important muscle attachment that has nothing to do with a tail.

https://evolutionnews.org/2015/02/from_the_steadi/

Thanks Dr. Wile. I always enjoy your blog for this very reason – news about interesting scientific discoveries! Since I have a background in medicine, this story makes me wonder if it will change things in the treatment of the various fluid disorders in the body. It will be interesting to see what develops going forward.

Many thanks Dr. Wile. God’s creation never ceases to amaze me and to bring glory to him… and I’m pretty sure that’s the point.

I think this is a good example of biased scientific report.

It smacks of desperation, doesn’t it?

The strange part is that I can not access the whole article through the PC, just by the smartphone.

I don not know either if anyone have the subscription here.(I don’t have it too, though I have access to the full article)

I really think it’s good if someone here could link(or do) a refutation to it.

Let’s start, just with the first part, the one that anyone may see, already starts biased: our cells are full of junk… I don’t if all you had the feeling that we went back to 2003, but I had. I wonder if someone had done his homework.

https://evolutionnews.org/2018/04/bad-design-or-bad-logic/

Love your blog , Dr. Wile. I value your knowledge . Do you, by chance, have a separate blog on the falsehood of evolution?

Thanks, Ron. This blog has categories, and evolution is one of them:

http://blog.drwile.com/category/evolution/

I finally remembered what this reminds me of: The Greek physicians who thought arteries conveyed air through the body. When arteries are cut, they said the air comes out – and since nature abhors a vacuum, blood gets sucked into the arteries from other places in the body, and we bleed.

About this link I think some people don’t understand this: “Some bad design examples are simply the natural consequences of good design decisions made elsewhere. All complex systems involve conflicting design requirements, so design tradeoffs must be weighed and carefully selected. As a result, decisions that are optimal for the whole may appear suboptimal with respect to a given subsystem or component. A good design to solve one engineering problem might easily exacerbate another engineering problem.” I say this, because, as the author said, some things may be good for the system in whole, but it’s not for other parts;this is called trade offs. In my opinion, those trade offs can be much better explained in a world here the inhabitants were affected by the Fall.

God Enlighten you all!

I mean, even these so called bad design and junk DNAs may be explained by the Fall.

I wasn’t quite sure where it was relevant to post this, so I decided Wonders of Creation was the closest category that fits my question. I was wondering if we can compare the artistry in creatures, such as the Picasso bug, the peacock, birds of paradise, for example, to human artistry and if there are enough similarities between the two to use the analogy of complex art only coming from a highly intelligent artist, such as the case when humans produce art, and complex artistry in animals, bugs, etc, only coming from an intelligent mind that understands art. I’m sorry if I didn’t quite word it right, and I’m hoping you catch what I’m trying to ask.

Certainly Darwin worried about it. He wrote, “The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!” However, I think most evolutionists would say that human artists have evolved to appreciate the things they have seen, and that art started as just trying to imitate what was being observed. As time went on, art “evolved,” but the initial building blocks of art are still recognizable. Thus, nature doesn’t do art. Instead, art was inspired by nature. That’s why they are similar.

Thanks for the reply Dr Wile. I can see what you’re saying from their perspective. How would you be able to test that hypothesis as an evolutionist? Can it be proven true or falsified?

That’s a good question. Evolutionists rarely worry about falsification, as they can always come up with “just so” stories to get around any conflicting data. Nevertheless, it would be great to come up with a way of testing the hypothesis. I can’t come up with one, however.

Honestly, I’m not exactly sure how to test the “just so” story either. It would seem difficult, because I’m not sure if we, at this point, fully recognize just how our brains interpret what should be considered complex and beautiful art, and what shouldn’t be considered complex and beautiful art, and how our brains would have developed such a fine distinction through evolutionary processes. I think most people recognize the peacock tail, when being displayed, intuitively, as a fine work of art, as Darwin certainly did, although I’m not sure if people know exactly why it should be considered a fine work of art. It’s an interesting discussion at any point, but difficult to prove or disprove in a creation/evolution debate, because I’m not sure how we test it, without getting into hypotheticals, from either a creationists or evolutionists position.