DNA is an incredibly complex molecule that can store information in an amazingly efficient manner. Experiments indicate that a single gram of DNA (a gram is approximately the mass of a U.S. dollar bill) can store 500,000 CDs worth of information! It uses a complicated system of alternative splicing so that a single region of the molecule can store the information needed to produce many different chemicals (see here and here, for example). It is so complex that even the best chemistry lab in the world cannot produce a useful version of it. In the end, the best human science can do is make tiny sections of DNA and then employ yeast cells to stitch those segments together so that they become something useful.

Over the past few years, DNA has surprised scientists with higher and higher levels of complexity. For example, scientists recently learned that DNA can store an extra level of information by slightly altering its typical shape. This was particularly surprising, because the fact that DNA alters its typical shape from time to time was already known. However, the alteration was thought to be the result of some kind of damage. We now know that it is not the result of damage. In fact, it is another level of complexity.

Even more recently, scientists discovered that DNA sometimes stores two completely different types of information in the same place. In some sections, it stores the recipe for making a chemical in the same place that it stores information regarding how often that chemical needs to be made. Once again, this was a complete surprise, because it was thought that the recipes for making chemicals were stored in certain sections of DNA, while the information regarding how often those chemicals should be made was stored in completely different sections. However, we now know that at least in some cases, both kinds of information are stored in the same place!

Well, DNA has offered up another surprise to geneticists, and it points to yet another level of sophistication in this incredible molecule.

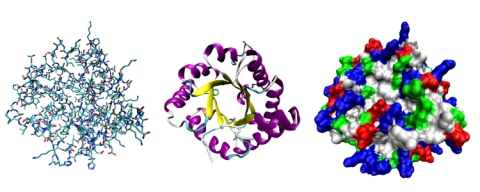

As far as scientists can tell, DNA is essentially a recipe book that tells each cell how to make chemicals called proteins and how often those proteins should be made. Proteins themselves are incredibly complex molecules, as shown in the image above. They are so complex that it takes several different illustrations to fully understand their structure and function. The three illustrations given above represent the same protein, but they are each designed to highlight a specific aspect of that protein. Without understanding all three of those aspects, a chemist will not be able fully understand the protein’s chemical nature.

It has long been thought that the protein recipes are stored in specific sections of DNA called genes. The sum total of genes in an organism’s DNA is sometimes referred to as the coding sections of DNA, since genes represent codes for making proteins. For most organisms, the coding sections of DNA make up only a tiny percentage of the total DNA, which initially led many evolutionists to suggest that the vast majority of human DNA is useless junk that was produced by evolution. Of course, as we have learned more about DNA, we have seen that this evolution-inspired idea is spectacularly wrong (see here, here, here, and here, for example). As a result, scientists now typically use the phrase “non-coding” DNA to describe what was once thought of as “junk DNA.”

Well, a recent study has shown that even the phrase “non-coding DNA” is not correct, at least for some sections. The researchers took 30 different types of human tissue and extracted all the proteins they could find from them. They then analyzed those proteins and linked them back to genes found in human DNA. In the end, they could identify more than 17,000 genes that were responsible for the proteins they extracted. However, they also found something incredibly odd: there were 193 proteins that could not be produced by any known gene in human DNA. Instead, their properties indicate that they were produced by sections of non-coding DNA!1

Assuming this study is correct, its results show us that we still don’t understand some of the most basic aspects of DNA’s function. If we can’t even tell which parts of the molecule code for proteins and which parts don’t, our understanding of how DNA works is clearly flawed. Of course, that’s not surprising. When I am faced with an intricately designed system, I might be able to figure out some aspects of the system. However, the more talented the designer, the more difficult it will be for me to fully understand the system. Since DNA was designed by the Ultimate Designer, we will probably never fully understand it. However, the more we do understand it, the more we can appreciate the amazing work that its Designer has done!

Now I will add one caveat. Proteins are so complex that they are incredibly difficult to analyze. In order to make the analysis process easier, the authors used enzymes to “cut up” the proteins they extracted into smaller pieces called peptides. They then used computer analysis to take the data collected from those smaller pieces and determine the proteins from which they came. It is possible that this analysis procedure produced some artifacts that might account for the 193 proteins which seem to come from the non-coding sections of DNA. It is also possible that there are actual genes for these 193 proteins, but they weren’t resolved in the human genome project. So while this study isn’t conclusive, its results are quite intriguing.

If the results of this research are confirmed, they demonstrate that we are a long way from understanding the amazingly-designed molecule we call DNA!

REFERENCE

1. Min-Sik Kim, et al., “A draft map of the human proteome,” Nature 509:575-581, 2014.

Return to Text