The Royal College of Physicians defines a vegetative state as:1

a clinical condition of unawareness of self and environment, in which the patient breathes spontaneously, has a stable circulation, and shows cycles of eye closure and opening that may simulate sleep and waking

When I read this definition, a question immediately arises: How do you know whether or not a person is aware of himself or his environment? You might ask him a serious of questions, but if he doesn’t have the ability to move his mouth or other parts of his body, how can he make you aware of his responses?

A few years ago, Dr Steven Laureys made headlines with his pronouncement that a man in a coma was able to communicate with people when given the aid of a keyboard and someone to support his hand as he typed. Based on Dr. Laureys’s work, it seemed that the man was describing exactly what you might think is going on in the mind of a person who is aware of himself and his surroundings but cannot communicate with the outside world. However, as skeptics started pointing out the flaws in Dr. Laureys’s method, further tests were done, and it turns out that the person supporting the patient’s hand was actually directing the patient’s hand. In other words, the patient wasn’t communicating; the helper was.

So what can we say scientifically about such patients? If they cannot do anything to communicate with the world, how do we know whether or not they are aware of it? A collaboration of scientists from Cambridge University, the University of California at Los Angeles, and the University of Western Ontario have gotten us a step closer to answering that question. They have published a study in the journal NeuroImage: Clinical that might help us produce a method by which an aware patient can communicate, even if he is not able to do so by traditional means.

In the study,2 the researchers compared eight healthy adults to 21 patients who had been diagnosed as being in a vegetative state or a minimally conscious state. In the main part of the study, they told the subjects to count the number of times they heard a particular word. Some subjects were told to count the number of times they heard the word “yes,” while others were told to count how many times they heard the word “no.” They then played a list of single-syllable words pronounced by a woman in an emotionless tone. While the list of words was being played, the researchers scanned the subjects’ brains with an EEG, which measures the the electrical activity over the scalp, and later a fMRI, which images the brain and attempts to determine what regions of the brain are active.

They found that the healthy subjects had distinctly different EEG and fMRI readings depending on the words that were heard. When they heard the word they were told to count, the EEG result had one pattern. When they heard irrelevant words, which the authors called “distractors,” the EEG pattern was quite different. Interestingly enough, they also found a third pattern. If the subjects were asked to count the word “yes,” the EEG pattern was unique when the word “no” was heard. The authors call this an “implicit” target word. It wasn’t the word that the subject was asked to count, but it was connected to that word by having the opposite meaning. Of course, the subjects ask to count the word “no” also had an implicit target word – “yes.” In the end, when the subject heard his or her implicit target word, an EEG pattern that was different from both of the other observed patterns emerged. Similar results were found with the fMRI readings.

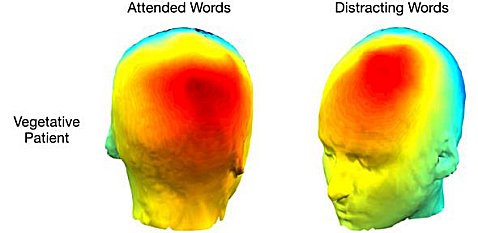

So in the end, healthy patients had three different EEG and fMRI readings, depending on whether the word played was the target word, the implicit target word, or the distractor. How did the vegetative and minimally conscious patients compare? 18 of them didn’t produce EEG or fMRI readings similar to the healthy patients, but three of them did. One of those three patients (P1) had results that were remarkably similar to those of the healthy patients in all three types of words. That patient’s results for the target word and the distractors are illustrated at the top of this post.

Another test they did on all the patients was to give them simple commands while asking them to imagine themselves playing tennis. While this was going on, they used an fMRI to image their brains. The patient P1 showed significant activity in the Supplementary Motor Area of the brain. This area has been shown to be active in other studies of healthy individuals who were asked to imagine themselves participating in sports. In the end, then, patient P1’s brain activity was very similar to the brain activity of healthy individuals under two different types of awareness tests.

Now here’s where it gets interesting. The researchers used the Coma Recovery Scale – Revised to assess the state of the patient. The lower the number, the less aware the patient is supposed to be. The 21 patients ranged in scores from 7 to 19. Guess what the score of patient P1 was. It was 7! Patients who have that score are said to be in a behaviorally vegetative state with no ability to follow commands. There was only one other patient in the study with that low a score. Despite his score, however, the study strongly indicates that patient P1 was, indeed, following commands. As the authors state:

This fMRI evidence of P1’s volitional abilities [the image produced when he was asked to imagine playing tennis] independently corroborated our EEG findings, and made a persuasive case for the presence of covert awareness in the behaviourally vegetative state.

I hope that this kind of research continues, because it seems to me that the assessment of whether or not a patient is truly aware of his or her surroundings is crucial when it comes to making the right health-care choices. In addition, such research might eventually make it possible for some patients who are considered vegetative to be able to communicate with their doctors and families!

REFERENCES

1. Working Group of Royal College Physicians, “The Permanent Vegetative State,” The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians 430:119-21, 1996

Return to Text

2. Srivas Chennua,Paola Finoiaa, Evelyn Kamau, Martin M. Monti, Judith Allanson, John D. Pickard, Adrian M. Owen, and Tristan A. Bekinschteine, “Dissociable endogenous and exogenous attention in disorders of consciousness,” NeuroImage: Clinical 3:450–461, 2013

Return to Text

This is so freaky…I have images in my mind now of organs being harvested, medical trials being run on coma patients, twice as bad, especially if they semi conscious.

Too many horror movies I know 🙂

Very interesting, thanks for the article.

Dr Wile,

My eldest son is disabled, while not by any means in a vegetative state – he is not able to communicate in any meaningful, that is specific way (grabbing a hand and taking one to the kitchen…)

I cannot help but think research along these lines may help a wider group communicate down the road.

You are right, Mark. By trying to get cues directly from the brain, I would think this line of research could help anyone who struggles to communicate effectively.