Why would you even think of using the Bible for science? It isn’t a scientific book!

It turns out that Discovering Design with Earth Science has two answers to that question. I shared them with him, and I thought I would share them with you as well. In the book, I present both sides of the age-of-the-earth issue in as unbiased a way as possible. I start with the uniformitarian view, which requires a very old earth. I then present the young-earth creationist view. The first answer to the atheist’s question is found at the beginning of that discussion:

Suppose you are examining the ruins of an ancient city and want to learn as much as you can about when it was built, how it was built, and how it fell into ruin. You see some of the remains of buildings, streets, walls, etc., but nothing has been preserved intact. You can learn a lot by investigating the ruins, but your conclusions will be based on your interpretation of what you see. Now suppose you found out that there was a book written shortly after the city was built, and it discusses the politics of the city for several centuries. While the focus of the book is on the government, it does cover many aspects of how and when the city was built.

Would you completely ignore the book and just examine the ruins, relying on your own interpretation to determine the city’s history? Of course not! If you wanted to learn the truth about the city’s history, you would read the book and let it help you interpret the ruins that you are investigating. This is how young-earth-creationists (YECs) study the geological record. They believe they have a book (the Bible) that comes from the Creator Himself. While the book focuses on more important things like salvation, morality, and our duties to God, it does discuss the creation of the universe, the earth, the organisms that lived on earth, etc. Since YECs consider the Bible to be an accurate source of history, they use it as a guide to studying the “ruins” of the geological column and fossil record. There’s a lot more to the history of the earth than what is in the Bible, but at least the Bible gives YECs a starting point to help their interpretation of the geological record.

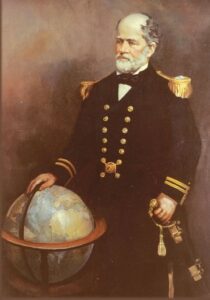

The second answer to the atheist’s question comes from my discussion of the surface currents found in the ocean. While others had mapped some of those currents (Ben Franklin, for example, mapped the Gulf Stream), the man most responsible for mapping the ocean’s surface currents was Matthew Fontaine Maury, who is pictured above. He was inspired to search for the “paths of the seas” that are mentioned in Psalm 8:8, and after an exhaustive research effort, he ended up producing a detailed map of those currents. This revolutionized ocean travel, so he became quite famous in his time. He ended up writing a very important text on oceanography (what they called “physical geography” back then): The Physical Geography of the Sea. In that book, he references the Bible several times. In my earth science book, I tell the students all of this and then I add:

Many scientists didn’t like that and tried to discourage him from connecting the Bible to science. In a speech given at the founding of The University of the South, he gave those scientists a stern rebuke:

I have been blamed by men of science, both in this country and in England, for quoting the Bible in confirmation of the doctrines of physical geography. The Bible, they say, was not written for scientific purposes, and is therefore of no authority in matters of science. I beg pardon! The Bible is authority for everything it touches.

(Diana Fontaine Corbin, A Life of Matthew Fontaine Maury, Samson, Lowe, et. al., 1888, p. 192)

Young-earth creationists like me really believe that. The Bible is an authority when it comes to all the important things of life: salvation, morality, our duties to God, etc. However, because it was written by the Creator Himself, we believe it is an authority in whatever it mentions, including science.

There’s so much that can be said about this, which I suppose is why you are writing a book about it. And not just this book exists, but many books. The atheist’s question really glosses over so many important category distinctions and begs the big question over the epistemology of scientific discovery and its limitations.

One category he glosses over is the usefulness of sources of information for scientific discovery. He might as well ask whether we can use any historical documentation for science. Take the discovery of the Hittites, for example. The Bible has long held information regarding the Hittites. Many scientists (A more concrete reference versus the less concrete objectification of “science”.) refused to acknowledge the Bible’s written evidence of the Hittites until tablets were discovered in ruins of Assyrian trade posts in Turkey that contained records of them.

Another category he glosses over is the understanding of what a “scientific book” is. Books which may be considered “scientific” could fall under a number of categories, all of which are written by someone who is reporting what they know, by testifying what they have observed or tests they have performed by some method of discovery that could be considered scientific at the time they wrote it. The purpose of “scientific” books may be for instruction, documentation, verification, or perpetuation. The Bible easily falls into these categories. It may be said that the Bible isn’t exhaustive, utilize modern scientific jargon, or engage modern scientific research. However, this is an anachronistic requirement and unrealistic for evaluating the truth claims of an ancient document.

Regarding the limitation of scientific discovery, the modern scientific academy limits epistemology only to evidence to the point where they won’t entertain the idea that something for which they can find no evidence should be concluded does not exist. so even the possibility that something may exist cannot be taken into consideration. Now this standard isn’t applied consistently, for there are some things that they consider may exist based solely on mathematical theory alone until such things may be disproven. This ignores the possibility that there may be a Creator who supersedes evidential discovery and requires for us that he reveal himself in order for us to know him. What standard of revelation can we possibly have? If he shows up in person in time and removes his presence, how will anyone who isn’t present at his coming know that his revelation was true except that it be written down? God has revealed himself many times throughout history, and these times have been written down. The next question would be how can we verify that these writings are accurate except they are self-authenticating? Without going into all the detail about that one, we can know that the Scriptures are self-authenticating. There is, therefore, an epistemological foundation beyond evidence, namely revelation. Scientists of old recognized revelation as true and accurate according to the standards of when they were written down. Many scientists today, even the scientific academy, do not recognize revelation because they limit epistemology to mere evidence.

Great post, thank you. I hadn’t heard about Maury.

Aside from the colloquial way of speaking about “science” being problematic, I think the problem here is theological, in that I’m not sure I’d say description of natural phenomena is what the Bible is for. It doesn’t need to be an authority in whatever it mentions for it to accomplish the thing for which it was sent. Further, being an “authority” is subjective, in that it depends on how its audience perceives it: For example, if I pretend the Bible is an authority in that everything it says is straightforwardly true, and then I come across some confusion in dates and orders of events in the Gospels, I will have been wrong. Of course, those issues aren’t actually a problem when you understand that things don’t have to be straightforward, but they’re the kind of thing the common atheist will bring up in his self-righteous confusion. Thus the problem is also one of teaching: What do people think “authority” means, and thus in what ways should we be careful how we talk so we don’t cause people to stumble?

I think there is also a contemporary tendency to overliteralize certain passages of scripture, like the prophetic passages—not to say this tendency hasn’t always existed, of course, but it has particular strength among American Evangelicals. I remember watching videotape lectures in church of Kent Hovind expounding on his vapor canopy, and I regularly have to trash copies of books in the Left Behind series I find in churches.

Bravo, Dr. Wile. What age will your new text be geared towards? I can’t wait for my son to read this. We are so enjoying your series and just finishing Science in the Scientific Revolution this year.

Blessings to you.

Thanks, Jim. The book I wrote last year (Science in the Atomic Age) is geared to 7th/8th grade, and this book is geared to 8th/9th grade.

Did this “frustrated atheist,” find any merit in your responses?

Not really, but at least he got two answers.