Some Christians don’t like quantum mechanics. More than 20 years ago, one Christian writer called it “the greatest contemporary threat to Christianity.”1 Eleven years ago, R. C. Sproul wrote a book entitled Not a Chance: The Myth of Chance in Modern Science and Cosmology. In that book, he attacked quantum mechanics. A Christian group called “Common Sense Science” champions an absurd model of elementary particles in order to get away from quantum mechanics.

Why all this Christian angst directed against quantum mechanics? Well, some Christians think that quantum mechanics is inconsistent with their view of God. For example, one of the fundamental conclusions of quantum mechanics is that the behavior of elementary particles and atoms is statistical, not mechanistic. This means that even if you knew everything there is to know about an atom, you could not predict exactly what that atom would do. You could make statistical statements like, “There is a 12% chance that it will do this and a 45% chance that it will do that.” However, there is no way to pin down exactly what an atom will do, regardless of how well you know the atom and everything that is affecting it.

This, of course, bothers many Christians, especially those of the Calvinist persuasion. Indeed, in the book I mentioned above, Sproul really seemed to think that quantum mechanics was somehow a threat to God’s sovereignty. If nature really is statistical at some level, then even God would not know exactly what His creation will do, and that just doesn’t work for a Calvinist!

Others don’t like quantum mechanics because, inherently, it doesn’t make sense. There is a lot in quantum mechanics that goes against common sense (as you will see in a moment), and since some people are under the mistaken view that science has to be rooted in common sense (as demonstrated by the website linked above), they think that there must be something wrong with quantum mechanics.

The problem is that when quantum mechanics is tested against the data, it passes with flying colors. Thus, even if you don’t like quantum mechanics, you must appreciate its scientific value. The experiment I will discuss below the fold is another clear example of this.

Take a point source of light and a screen, and then put a wall between them. Now put two tiny slits in the wall. What will you see on the screen? Most people think you will see something like this:

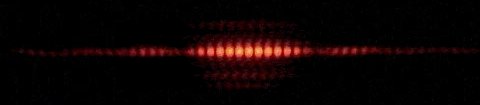

That’s what makes sense, right? The light shines through each slit and lights up the area on the screen right across from each slit. However, that’s not what you see. Instead, you see this:

Why do you see so many patches of light and dark coming from just two slits? Because light can behave as a wave, and when a wave passes through two slits, it produces two waves (one from each slit), and those waves can interfere with one another. In some places, the two waves will add together to make an even brighter light (and that’s where you see bright patches on the screen). In other places, they will cancel each other out (and that’s where you see dark patches on the screen).

What does this tell you? It tells you electrons can act as a wave. This kind of experiment has been done with many particles, and it even works with relatively large molecules.2 So even relatively large molecules can act like waves.

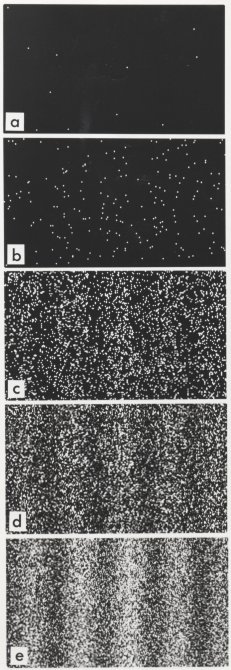

Now here’s the really crazy part. Take that same electron source and adjust it so that only one electron hits the wall at a time. Guess what happens? You get exactly the same interference pattern. So it’s not that two electrons (or two photons or two molecules) interfere with each other as they pass through the slits. Each electron (or photon or molecule) seems to interfere with itself, implying that each electron (or photon or molecule) passes through both slits at the same time! This makes no sense whatsoever, but it’s what the data say.

For a long time now, physicists have been studying these kinds of experiments, and they have been using quantum mechanics to understand them. One thing that quantum mechanics says is that every particle can be described by an equation called a wave function. In 1926, Max Born postulated that the square of that wave function at any given point in space represents the probability of finding the particle there. Notice that this is where the statistical nature of quantum mechanics comes into play. The wave function cannot tell you where the particle is. Instead, it can only tell you the probability of it being in a given place.

Well, Born’s interpretation leads to a very important prediction when it comes to interference experiments like the ones I have been describing. It says that if you add more slits to the experiment, you will get a more complicated interference pattern, but it will really only be all possible combinations of a two-slit interference pattern. In other words, while particles can interfere with themselves as if they are coming from two separate locations, they cannot interfere with themselves as if they are coming from three or more separate locations.

While this prediction follows from the mathematics of quantum mechanics and Born’s interpretation of the wave function, it has never actually been tested…until now. Sinha and colleagues did a three-slit interference experiment with light. They constructed the experiment so that they could close each slit independently. With this configuration, there are eight possible ways to run the experiment with at least one slit open. For example, all three slits could be open, just the leftmost slit could be open, the two end slits could be open but the middle on closed, etc. They showed that the result they got when all three slits were open was just the sum of the other seven possibilities. This showed that the light was really only using two slits to interfere with itself – a confirmation of the prediction.3

This is important, because the prediction comes from a specific interpretation of the wave function – an interpretation that tells us the wave function can only give you probabilities, not absolutes. While these results don’t prove Born’s interpretation to be right (indeed, science cannot prove anything), they certainly lend support to it.

Christians who wish to be rational must follow the data wherever they lead. Of course, science is far from perfect, and experiments that produce data can be flawed. Thus, all conclusions of science must be tentative. However, we cannot reject theories because we don’t like them or because they do not conform to our view of God and His creation. As unpalatable as quantum mechanics is to some Christians, it is currently the best description we have of the atomic and molecular world. These most recent data simply add more evidence to the pile.

REFERENCES

1. Allen Emerson, “A Disorienting View of God’s Creation,” Christianity Today, February 1,1985, p.19.

Return to Text

2. Nairz O, Arndt M, and Zeilinger A., “Quantum interference experiments with large molecules,” American Journal of Physics, 71:319-325, 2003

Return to Text

3. Urbasi Sinha, et al., “Ruling Out Multi-Order Interference in Quantum Mechanics,” Science, 329:418-421, 2010 (Abstract available online)

Return to Text

I am going to break with tradition and suggest that quantum mechanics far from being contrary to Christianity is really like what Christians should have expected. Naturalism claims that reality is perfectly understandable and deducible by the human intellect. But Christianity while maintaining that God would create an orderly world should expect that when we tried to understand things completely we would reach a place where we would come up against things that are beyond our ability to understand (what God understands we cannot know). If God is three in one, should we be surprised if light is both waves and particles.

Mike, thanks for the insightful comment! You are quite right. I had never thought of comparing particle/wave duality to the Trinity. Very nice.

I think it’s a bit backward for a Calvinist to assume that because we can’t comprehend or quantify such tiny things God is bound by the same inability.

I am a calvinist, and like Mike, I think quantum mechanics strengthens our argument. The calvinist does not say this is going to happen, and therefore God sees the future by reading the motion of particles. Instead, God knows what will happen, therefore the particles will move in a certain way, even if scientifically, there is a chance that they move a different way.

To us, there will always be the appearance of chance. But God knows what will happen, and therefore he isn’t just hoping that you will get saved.

Thanks for your comment, Jonathan. I am not a Calvinist, but I agree that there is no need to say that quantum mechanics is a threat to Calvinism.

thanks

You are welcome, Jonas.

As with Jonathan, I am also a Calvinist. I agree with him that there is no threat posed against God’s sovereignty by the fact that nature is at least somewhat statistical. This in no way implies that God does not know what His creation will do. In fact, if God did not know what His creation would do, He would not be God. Just because it seems like quantum mechanics requires atoms to act by chance does not mean that God has no control over them. Looking to the Bible for an example of this, let’s take the practice of casting lots. If anything seems to humans as left up to chance, it is the casting of dice. Any statistics course uses dice as a simple example of how statistics works. However, Proverbs 16:33 says “The lot is cast into the lap; but the whole disposing thereof is of the Lord.” We may be able to explain how the world works in terms of statistics, but the Lord is yet in control of what event actually takes place.

Thank you for posting this. I appreciate you sharing that we don’t need to be afraid of quantum mechanics—or science in general, for that matter. All true science lines up with the Bible. And, as long as our faith is in Christ and not in science, we don’t need to fear what science may discover.

Thanks for the excellent comment, Stephanie. I had never thought of comparing quantum mechanics to casting lots, but you are exactly right. Casting lots seems random to us, but it need not be random to God.

I never knew there were any arguments against quantum mechanics from Calvinism, but it sounds as though that anyone who seriously argues against it on theological grounds may be over philosophizing the subject. It’s a matter of the current operation of the physical universe, not a matter of contradicting history in general or the Bible in specific. As far as the whole predestination versus free-will argument goes, I think people waste too much time (assuming they have the freedom of will to choose how to spend their time, otherwise they’d have been predestined to forever argue in circles.)

Ben, I am left to wonder whether I choose to like your comment or am simply predestined to do so…

Easy. You were predestined to choose to like his comment.

Ah…it’s so obvious!