One of the common predictions made by people who believe in catastrophic global warming (aka “climate change”) is that as the globe’s temperature rises, there will be more and more droughts. As one book on global warming puts it:1

Extreme drought is one of the expected consequences of increased global warming, especially in the American Southwest, where it has already been projected to be severe by several models.

I have already written about the fact that actual observations show the precise opposite for the American Southwest. But what about the globe as a whole? Perhaps the American Southwest is not behaving as global warming enthusiasts predicted, but that doesn’t mean droughts aren’t increasing in other parts of the world. Surely the global warming that has already happened has produced drier conditions on the earth as a whole, right? After all, that’s what the climate modelers have predicted.

For example, the British government funded a study on global warming and drought by climatologists at the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research. The study, which was published in 2006, made the following prediction:2

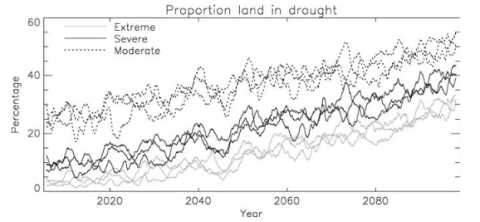

(image from reference 2)

Notice that the amount of land around the globe which experiences moderate to extreme drought was projected to increase in a shaky but consistent fashion throughout the 21st century. Is that what’s actually happening?

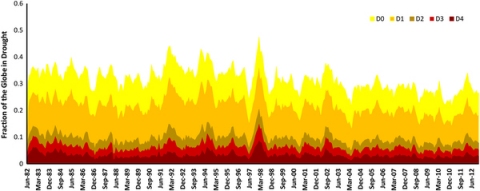

The answer is, “No.” A recent study from the University of California Irvine was published in the Nature journal that is aptly named Scientific Data. The authors integrated data on soil moisture and precipitation from several different sources for June of 1982 through June of 2012. They characterized droughts with 5 different levels (D0-D4), with D0 being the mildest of droughts and D4 being the most severe. Here are their results:3

Notice that there has been very little change in the percentage of the globe experiencing drought over this 30-year time period. While clearly not statistically significant, the only trend seen in the data is a slight decrease in the percentage of land that experienced drought.

If global warming is really supposed to be happening, as many scientists and politicians assure us, where is the increase in drought that is supposed to accompany it? Of course, one possible answer is that global warming hasn’t gotten severe enough to produce an increase in droughts. As time goes on and global warming increases, the droughts will follow. There are two other possibilities, however:

(a) Global warming is not really happening, at least not in any way that will affect global climate in a significant fashion.

OR

(b) Global warming will not affect the frequency or severity of droughts.

I find either of those two possibilities to be much more likely.

REFERENCES

1. Julie Kerr Casper, Global Warming Trends: Ecological Footprints, (Facts on File, Inc. 2009), p. 157.

Return to Text

2. Burke, Eleanor J., Simon J. Brown, Nikolaos Christidis, “Modeling the Recent Evolution of Global Drought and Projections for the Twenty-First Century with the Hadley Centre Climate Model,” Journal of Hydrometeorology, 7:1113–1125, 2006.

Return to Text

3. Zengchao Hao, Amir AghaKouchak, Navid Nakhjiri and Alireza Farahmand, “Global integrated drought monitoring and prediction system,” Scientific Data doi:10.1038/sdata.2014.1, 2014.

Return to Text

Sorry Jay, but you can’t fool climatologists living in the American southwest, particularly if you are willing to cite papers that contradict your opinion on drought and global warming. All of the indicators here (from PDSI to hydrological storage, etc.) show enhanced drought over the past few decades, including warmer winters with reduced snowpack (most important to the human side of things). The physics behind this are fairly simple: poleward displacement of the polar jet stream and enhanced strength of the eastern Pacific anticyclone, both consequences of a warming climate, result in fewer storms reaching land in the American southwest. Hence the precipitation patterns in recent seasons:

http://www.climatecentral.org/news/8-images-to-understand-the-drought-in-the-southwest-16149

ENSO is a major factor in blurring drought trends, because of its heterogeneous impact on regional climate in the American southwest. The more frequent warm phases (El Nino) tend to mitigate drought in some areas while making it worse in others. This needs to be controlled for if you really want to talk about drought in the southwestern US. As for the rest of the world, try telling farmers in the Volga and Black Sea regions that global warming hasn’t impacted drought severity…

Also, you can’t use the drought indices used by Hao et al. (2014) to contradict the model predictions by Burke et al. (2006). The former uses a different measure of drought severity. Why didn’t you just cite Figure 6 in Burke et al. (2006), which (using modeled/observed PDSI) demonstrates that their model accurately reconstructs drought trends in the 20th century and that **the land area affected by drought has more than doubled since 1980**! Regardless, Hao et al. (2014) never draw the same conclusion as you, that trends in global drought contradict model predictions of AGW. Wouldn’t that be worth mentioning, if it were true?

On the contrary, Damberg and AghaKouchak (2013; the latter author is a co-author of Hao et al., 2014) write:

“We investigate the spatial patterns of the wetness and dryness over the past three decades, and we show that several regions, such as the southwestern United States, Texas, parts of the Amazon, the Horn of Africa, northern India, and parts of the Mediterranean region, exhibit a significant drying trend.”

http://amir.eng.uci.edu/publications/13_Drought_Trend_TAAC.pdf

Please don’t tell us that climate models fail against real world data and then go on to cite papers that contradict your very claim. It’s poor taste.

Thanks for your comment, Jon. I would like to reproduce the full quote from Damberg and AghaKouchak, rather than the truncated one that you posted. Here is what they say:

In other words, their results show once again that the the global warming model predictions are not lining up with the data when it comes to the amount of the globe in drought. This agrees with other studies that say the same thing.

I agree that in the Burke et al paper, the authors show agreement between observations and their model from 1952 to 1998. Since their paper was written in 2006, however, that’s not much of a feat. It’s easy to get a model to reproduce specific past trends. In addition, the data set they use employs only monthly surface air temperature and precipitation to calculate drought. The data set employed by Hao et al uses precipitation and soil moisture, which are better indicators of drought. So in the end, the better the data, the worse the global climate models do. I also agree that in the Burke et al, they use a different definition of drought than what is used in the Hao et al paper. However, regardless of the severity in either paper, Burke et al say that droughts should increase. Hao et al show that they have not.

I also agree that the Southwest is experiencing a major drought right now. However, the data seem to indicate that it is not unusual and does not represent a trend. In the climate depot link you gave, the graphs in which they see trends look at specific regions of the Southwest (water storage in Elephant Butte, NM, SPEI for NM, evapotranspiration in AZ, etc.) The paper I cite in my discussion uses 22 sites from various parts of the Southwest. This, of course, produces a much better view of the region as a whole, and once again, it disagrees with the climate models, as most observations do. Now, at the same time, the Damberg and AghaKouchak study does show a drying trend in the American Southwest. It will be interesting to see how this plays out as more observational studies are done.

From a global perspective, however, the studies agree that there is no global trend in droughts, which is in direct disagreement with global climate model predictions.

Well, there’s another prediction out the window. What’s next? Tidal waves maybe?

I appreciate these articles, Dr. Wile. They help to balance out the half-truths and even outright falsehoods of the media.

My pleasure, Jacob. I am glad you find the posts useful.

Thank you so much for your thoughtful response to Jon’s critique. This is why I often find the comments portion of your posts even more enlightening than the post itself.

As a person with limited science background, I accepted your statements without questioning because of your record of objective, reasoned commentary. However, when I read Jon’s comments I was tempted to think, “Whoa, sounds like Dr. Wile’s playing fast and loose with the facts and Jon called him out!”

Thankfully, Jon chose to post his comments on your blog instead of as some rant on his own personal corner of the web. This allowed you the opportunity to give a response. The end result was that this exchange enhanced my understanding of the topic and restored my faith in you scholarship (it wasn’t really in doubt).

Thank you Dr. Wile and thank you Jon for letting the rest of us “participate” in your this exchange (although, Jon, I think you could learn from Dr. Wile’s demeanor in expressing your disagreement).

It never fails to amuse me how easily Dr. Wile counters those who attempt to debate him. It boggles my mind that these Climate Change alarmists insist on clinging to their ideas, despite the fact that all they have to look forward to is more failed predictions.

Dr. Wile, have there actually ever been models about Climate Change that have succeeded in their predictions?

Zorcey, I don’t know of any that have succeeded in their predictions, at least not when it comes to things like average global temperature, drought, etc. Of course, that isn’t very surprising. There is a lot we don’t know when it comes to climate dynamics. Hopefully, as we learn more, the models will become more reasonable, and as a result, their predictions will be more accurate.

Dr. Wile,

My citation from Damberg and AghaKouchak was directed to the topic of drought trends in the American southwest. Of course it is truncated (so is yours). 🙂 Hence I provided the link, so anyone could pull up the full paper if desired.

Copying a larger (but still truncated) portion of the abstract doesn’t negate my point that the authors confirmed the predicted drying trend for the American southwest in response to global warming. Neither does your citation of McCabe et al. (2010), who looked only at precipitation trends (not drought). The statistically significant increases in drought for the American southwest are attributed largely to increased temperature (no argument there) and a reduction in the snow vs. rain at high-elevation sites. As I mentioned in my comment, ENSO is a complicating factor, because the anomalously more frequent warm phases brought higher precipitation to much of the southwest, which mitigated the long-term drying trend. As Lloyd initially suspected, you are indeed playing fast and loose with the facts.

Assessing drought trends in the southwest takes far more effort than picking a couple of key articles that you believe support your skepticism. We understand rather well the climate dynamics behind enhanced drought in the American southwest, and putting the modern droughts in a paleoclimate perspective (specifically, the last 2 ka) supports the now robust conclusion that the southwest already has and will continue to suffer more drought in response to global warming. The following assessment provides a fairly detailed summary:

http://swccar.org/sites/all/themes/files/SW-NCA-color-FINALweb.pdf

Affirming that together, relatively steady precipitation and warmer temperatures have enhanced regional drought, the authors further note:

“Various other hydrologic changes in the Southwest symptomatic of a warmer climate occurred between 1950 and 1999 (Barnett et al. 2008). These include declines in the late-winter snowpack in the northern Sierra Nevada (Roos 1991), trends toward earlier snowmelt runoff in California and across the West (Dettinger and Cayan 1995; Stewart, Cayan, and Dettinger 2005), earlier spring onset in the western United States as indicated by changes in the timing of plant blooms and spring snowmelt-runoff pulses (Cayan et al. 2001), declines in mountain snowpack over Western North America (Mote et al. 2005), general shifts in western hydroclimatic seasons (Regonda et al. 2005), and trends toward more precipitation falling as rain instead of snow over the West (Knowles, Dettinger, and Cayan 2006).

These various indicators have recently been studied in an integrated program of hydroclimatic trends assessment for the period 1950–1999. The research findings for a region of the Western United States demonstrated that during this period human-induced greenhouse gases began to impact: (a) wintertime minimum temperatures (Bonfils et al. 2008); (b) April 1 snowpack water content as a fraction of total precipitation (Pierce et al. 2008); (c) snow-fed streamflow timing (Hidalgo et al. 2009), and (d) a combination of (a), (b), and (c) (Barnett et al. 2008). These evaluations also indicated, with high levels of statistical confidence, that as much as 60% of the climate-related trends in these indicators were human-induced and that the changes—all of which reflect temperature influences more than precipitation effects—first rose to levels that allowed confident detection in the mid-1980s.”

As far as global drought trends, I realize the indicators are more difficult to assess, but they don’t support your claim. First, you write:

“I agree that in the Burke et al paper, the authors show agreement between observations and their model from 1952 to 1998. Since their paper was written in 2006, however, that’s not much of a feat.”

But the point is, the observational data against which they verified the model already show an increase in areal extent of drought. So I asked, why not include that graph (even if you think Hao et al.’s data are better) to show that studies do exist, which have reconstructed an increase in global drought from observational data? You should add to that list Dai (2011; 2012), who derived the same global drought increase using PDSI, but also considered soil moisture and GRACE satellite measurements. He concludes:

“The global dry areas have increased by about 1.74% (of global land area) per decade from 1950 to 2008. The use of the Penman‐Monteith PE and self‐calibrating PDSI only slightly reduces the drying trend seen in the original PDSI… The recent widespread drying trend and the effect of surface warming are qualitatively consistent with the observed decreases in streamflow over many low and midlatitude river basins [Dai et al., 2009]. Our PDSI trends are broadly comparable with those in the soil moisture simulated by another land surface model [Sheffield and Wood, 2008a]. The results are also consistent with the model‐predicted 21st century climate, which shows severe drought conditions by the middle of this century over most low and midlatitude land areas [Wang, 2005; Sheffield and Wood, 2008b; Dai, 2011]. Thus, I believe that our main conclusion is robust that recent warming has caused widespread drying over land. And model predictions suggest that this drying is likely to become more severe in the coming decades [Dai, 2011].”

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2010JD015541/abstract

As you point out, Damberg and AghaKouchak (2013) do not reach the same conclusion in terms of global drought trends (though neither do they show a decline in drought..), but they *do* confirm a significant drought increase in the southern hemisphere and for many individual regions (including the American southwest) where enhanced drought is predicted by models of AGW.

Your claim that “the better the data, the worse the global climate models do” is a little misleading. Though Hao et al. reconstruct no significant drying trends for the entire globe, their focus is to forecast global drought as it pertains specifically to agricultural sustainability. Hence, they employ a multivariate index of drought most relevant to agriculture. But for the climatologist (like myself), interested in how a warming climate will the hydrological cycle, effective moisture, etc. the historical reconstructions of drought trends by Dai, Burke, Damberg, AghaKouchak, and numerous others using meterological and climate indicators, are far more relevant and compelling. Some of the drought indicators employed by Hao are affected by land and water management as much as climate. Hao et al. can tell us when and to what extent are crops are in danger, but they cannot assess the question of how global warming has impacted the hydrological cycle and effective moisture over the land surface.

Thanks for your reply, Jon. My conclusion that there is no increasing drought in the American Southwest isn’t just based on one study. The PDSI for the American Southwest confirms that there is no trend in droughts for that region:

http://www.inkstain.net/fleck/wp-content/uploads/swpdsimultigraph.png

Even the article you cite shows in Figure 1.3 that the aridity of the American Southwest is not unusual on a much larger timescale. So while some studies (like Damberg and AghaKouchak) do indicate a drying trend in the American Southwest, the bulk of the data do not. This is precisely why I said, “It will be interesting to see how this plays out as more observational studies are done.”

Of course, the global data strongly refute your claims. Yes, the Burke et. al. paper was able to fit some data that had already been measured, but as I already stated, the data were not very indicative of drought, because they didn’t include soil moisture. In addition, while Dai was able to force a small amount of increase in global drought, Sheffield has shown that his approach is not rigorous enough to draw that conclusion. Indeed, Sheffield says:

This, of course, agrees with the data of Hao et. al. as well as Damberg and AghaKouchak. Speaking of the latter, I find it interesting that you say, “the historical reconstructions of drought trends by Dai, Burke, Damberg, AghaKouchak, and numerous others using meterological and climate indicators, are far more relevant and compelling.” Nevertheless, you reject Damberg and AghaKouchak’s data when it comes to global drought. If their data are so compelling, why do you disregard it on a global scale, especially when it agrees with the bulk of the data?

In reference to your response to Zorcey, the data clearly show that global climate models have not produced accurate predictions. For example, Douglass et. al. compared 22 models’ prediction to the data. They find:

Now as I told Zorcey, models will get better as we learn more, but right now, their predictions are, by and large, horrendous when compared to the actual data.

Zorcey,

It’s nice that you are amused by comments and critiques, but I’ll admit that it boggles my mind as well how badly misinformed much of the internet is when it comes to climate change. As an active researcher in paleoclimatology, I am absolutely astounded that you believe climatologists have offered no confirmed predictions regarding an anthropogenically forced climate. Every year, the amount of research supporting this concept grows exponentially. We find that trends in global and regional air temperature, ocean temperature, sea-ice extent, glacier length, overall hydrological activity, and local aridity (to name a few) have conformed to what models predict as a response to global warming. Science doesn’t expand and progress like this over series of failed predictions. I’m sorry to hear that someone has pulled the wool over your eyes, and I regret that climatologists have not been more successful in communicating these ideas to the public. I regret more than certain others have paid billions to impede the process…

Lloyd,

I’m glad you appreciate my posting comments here rather than on my own blog (of course, Dr. Wile would be free to comment there as well). In any case, I’ve seen Dr. Wile’s demeanor in responding to those who disagree with him, so you could say that I learned from him. 😉

Jon,

I greatly enjoy debate, so yes, critiques and comments amuse me a good deal.

In response to your statement that I have “the wool pulled over my eyes,” and that people on the Internet are “badly misinformed” (I assume I was being grouped with them), I must admit I resent that (at the very least the former). While I don’t pretend to be a climatologist, I do my very best to extensively research any topic I find myself interested in. I trust Dr. Wile’s arguments to be of integrity because I read the data he cites, and always find it in alignment with what he is saying. I have yet to discover a case where he has fumbled the facts or quoted out of context.

As for my beliefs that models for predicting changes in the climate are almost always wrong, I’ll have to stick by that. I mean no offense, but your comments have given me no reason to reconsider my position on the matter. I’ll admit I’m biased – as we all are – but I like to think a good piece of evidence would at least intrigue me. Your citations have failed to do so, as they seem to be at odds with the majority of the data.

Dr. Wile, could you give the full title of the Douglass et al paper? I couldn’t access it because Wiley Online is doing maintenance. Thanks…

S.M., the reference is:

Douglass, D.H., et. al., “A comparison of tropical temperature trends with model predictions,” International Journal of Climatology, doi:10.1002/joc.1651, 2007