(image from the paper being discussed)

A few months ago, I discussed the acidification of the ocean. It is often called global warming’s “evil twin,” because it is caused by rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. Unlike global warming, however, the connection between carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere and increasing ocean acidity is straightforward and has been confirmed by many observations. Thus, while it is not clear that increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide will lead to global warming, it is very clear that increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide lead to an increase in the acidity of the ocean.

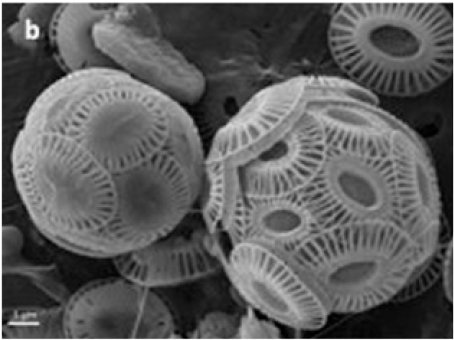

The question is, “How will increased ocean acidity affect the organisms living there?” Many who call themselves environmentalists answer that question by saying increased ocean acidification will produce catastrophic results, threatening many species of ocean life. The reason? Many organisms that live in the ocean have shells made out of calcium carbonate. To make those shells, the organisms use carbonate ions that are dissolved in the seawater. However, as the acidity of ocean water increases, the concentration of carbonate ions in the water decreases. Thus, it is thought that increased ocean acidification will make it harder for these organisms to make their shells. Here’s how one publication from the National Academies puts it1

As ocean acidification decreases the availability of carbonate ions, these organisms must work harder to produce shells. As a result, they have less energy left to find food, to reproduce, or to defend against disease or predators. As the ocean becomes more acidic, populations of some species could decline, and others may even go extinct.

Now if that’s true, ocean acidification is a major problem. Indeed, if several shell-making organisms go extinct, we could be in real trouble.

However, this is a very simplistic way of looking at things. Yes, the availability of carbonate in the ocean will affect how easily shell-making organisms produce their shells. However, there are a host of other factors involved in the process. To single out one factor without considering the others is not very scientific. When all the factors are considered, the picture is not nearly as bad.