As I mentioned in two previous posts (here and here), the coordinated release of scientific papers from the ENCODE project has produced an enormous amount of amazing data when it comes to the human genome and how cells in the body use the information stored there. While the majority of commentary regarding these data has focused on the fact that human cells use more than 80% of the DNA found in them, I think some of the most interesting scientific results have gotten very little attention. They are contained in a paper that was published in a journal named Genome Biology, and they relate to the pseudogenes found in human DNA.

For those who are not aware, a pseudogene is a DNA sequence that looks a lot like a gene, but because of some details in the sequence, it cannot be used to make a protein. Remember, a gene’s job is to provide a “recipe” for the cell so that it can make a protein. Well, a pseudogene looks a lot like a recipe for a protein, but it cannot be used that way. Think of your favorite recipe in a cookbook. If you use it a lot, it probably has stains on it because it has been open while you are cooking. Imagine what would happen if the recipe got so stained that certain important instructions were rendered unreadable. For someone who has never looked at the recipe before, he might recognize that it is a recipe, but because certain important instructions are unreadable, he will never be able to use the recipe to make the dish. That’s what a pseudogene is like. It looks like a recipe for a protein, but certain important parts have been damaged so that they cannot be used properly anymore. As a result, the recipe cannot be used by the cell to make a protein.

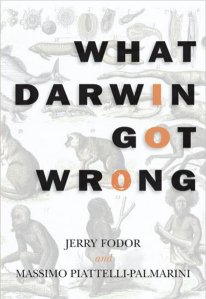

Pseudogenes have been promoted by evolutionists as completely functionless and as evidence against the idea that the human genome is the result of design. Here is how Dr. Kenneth R. Miller put it back in 1994:1

From a design point of view, pseudogenes are indeed mistakes. So why are they there? Intelligent design cannot explain the presence of a nonfunctional pseudogene, unless it is willing to allow that the designer made serious errors, wasting millions of bases of DNA on a blueprint full of junk and scribbles. Evolution, however, can explain them easily. Pseudogenes are nothing more than chance experiments in gene duplication that have failed, and they persist in the genome as evolutionary remnants…

Obviously, Dr. Miller didn’t understand intelligent design or creationism when he wrote that, as they can both explain nonfunctional pseudogenes. Before I discuss that, however, I need to point out that since 1994, functions have been found for certain pseudogenes. As far as I can tell, the first definitive evidence for function in a pseudogene came in 2003, when Shinji Hirotsune and colleagues found that a specific pseudogene was involved in regulating the functional gene that it resembles.2 Since then, functions for several other pseudogenes have been found. In fact, a recent paper in RNA Biology suggests that the use of pseudogenes as regulatory agents is “widespread.”3

Even though functions have been found for many pseudogenes, the question remains: Are most pseudogenes functional, or are most of them non-functional? Well, based on the ENCODE results, we might have the answer. While the ENCODE results indicate that the vast majority of the genome is functional, they also indicate that the vast majority of pseudogenes are, in fact, non-functional.

Continue reading “The ENCODE Data and Pseudogenes”