(Credits:Beavercheme2, Aga Machaj, Univ. Missouri-Columbia)

Yesterday, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that the Nobel Prize in chemistry will be shared among three scientists who all used directed evolution to engineer proteins that solve problems. A reader who saw a news story about the announcement asked me to explain what “directed evolution” means, and I am happy to oblige. In directed evolution, scientists use the concepts of variation and selection to take a molecule that already exists in nature and adapt it to do something that they want it to do. Using a concrete example that comes from the research of Dr. Frances Arnold (one of the recipients) is probably the best way to explain the process.

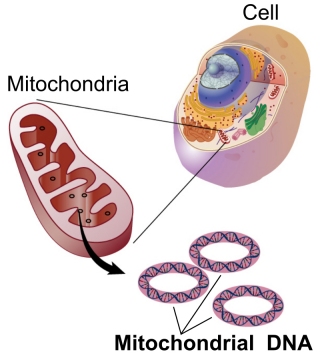

Dr. Arnold’s lab started with a naturally-occurring enzyme charmingly named P450 BM3. Enzymes speed up specific chemical reactions, and P450 BM3 speeds up the reaction in which an oxygen atom is inserted between a carbon atom and a hydrogen atom in a fatty acid molecule. This is an important step in the process by which a living organism breaks down fatty acid molecules. Dr. Arnold’s lab was interested in doing the same kind of reaction, but on a different type of organic molecule: a small alkane. The enzyme P450 BM3 couldn’t initially do that. However, it could weakly speed up that reaction on large alkanes.

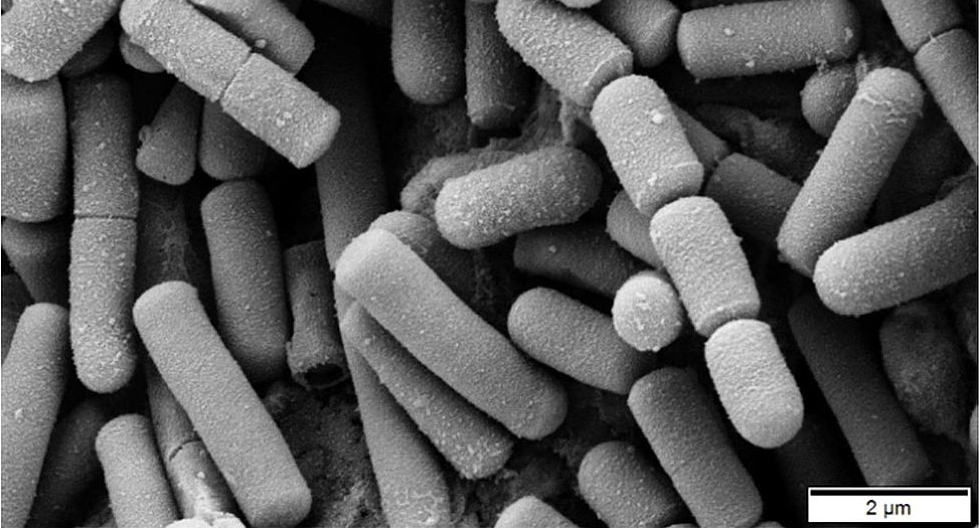

Since the enzyme could at least do that, Dr. Arnold thought that she could “tweak” it until it did exactly what she wanted it to do. However, enzymes are absurdly complicated molecules, and human science isn’t very good at making or understanding them. So she decided to let better organic chemists (bacteria) do the heavy lifting. Her lab took the gene that tells bacteria how to make P450 BM3 and subjected it to mutations. They then saw whether or not the resulting enzyme made by bacteria was any closer to being able to do what they wanted it to do. Maybe it did a better job speeding up the reaction on a large alkane, or maybe it was able to speed up the reaction on a shorter alkane. If that was the case, they saved that gene and allowed it to mutate more, seeing if any more progress could be made. If not, they threw it away and tried again.

This is why the process is called “directed evolution.” Dr. Arnold’s lab induced mutations (which are a source of genetic change in organisms) and then selected any enzyme that ended up being better at what they wanted it to do. With enough of those steps, they were able to get what they wanted: an enzyme that inserted an oxygen atom between a carbon atom and a hydrogen atom in a small alkane. In the end, the process had changed just over 2% of the molecule, but that was enough to change it from an enzyme that acted on fatty acids to one that acted on small alkanes.