One of the most important things a cold-water animal must deal with is how the temperature affects certain proteins that govern the response of the nervous system. Cold temperatures tend to reduce the efficiency of those proteins. As a result, the colder the water, the slower the nervous system conducts signals. In very cold water, the slowdown would be so great that in the end, signals would not travel quickly enough to allow the animal to do what it must do in order to survive.1 Thus, it has always been assumed (reasonably so) that many nervous system proteins in cold-water animals are significantly different from the corresponding nervous system proteins of animals that do not frequent cold waters.

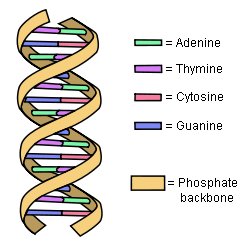

Garrett and Rosenthal decided to determine just how different such proteins are by comparing the genes of an Arctic octopus (genus Pareledone) to that of a tropical octopus (Octopus vulgaris). Since genes tell the octopuses’ cells how to make the proteins they need, the researchers assumed that whatever differences exist in the nervous system proteins would show up in the genes that produce those proteins. Once again, this is a completely reasonable assumption. However, their study shows that the genes involved in producing these nervous system proteins are nearly identical between the species.2 To confirm this, they injected the genes from the different species into frog egg cells, and they found that the frog egg cells used those genes to produce nearly identical proteins. So in the end, the genes that produce those nervous system proteins are essentially the same in both species. But that doesn’t make sense. The proteins have to be different.

Well, it turns out they are different, but not because of the genes that produce them!

Continue reading “Octopuses Can Change the Products of Their Genes When Necessary!”