The MSN headline is attention-grabbing, to say the least:

The Universe Should Not Actually Exist, Scientists Say

One of the things my Ph.D. advisor stressed over and over again is that there are two phrases any good scientist should be very comfortable saying. The first is, “I don’t know.” The second is, “I was wrong.” I have uttered both of those phrases throughout my career, and I am very glad that in this case, the scientists mentioned in the headline are wrong!

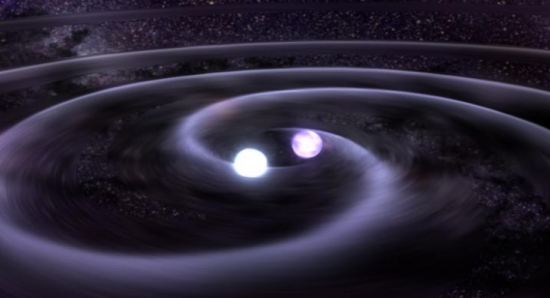

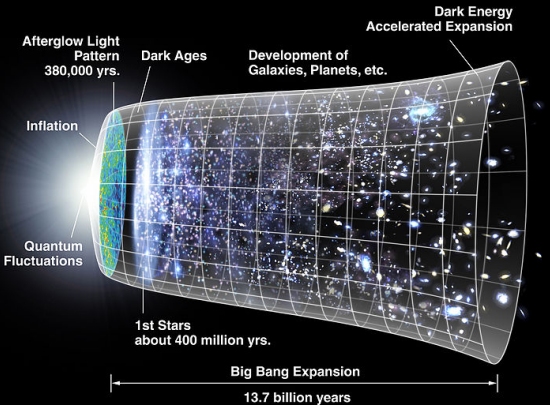

So why do these scientists say the universe shouldn’t exist? Well, if you don’t want to believe in a supernatural Creator, you have to figure out where the universe came from. Experiments demonstrate that even empty space contains a certain amount of energy, and our current understanding of quantum mechanics says that it is possible for energy to spontaneously be converted into particles. This is often called a quantum fluctuation, and for those who don’t want to believe in a supernatural Creator, it is a way of explaining how the universe got started. Particles sprung into existence from the energy of empty space, producing the universe we see today.

If this seems strange to you, don’t worry. You aren’t alone. As a nuclear chemist, I am well-versed in quantum theory and have no problem with the concept of particles springing into and out of existence in empty space. Nevertheless, the idea that this process can produce a universe is very strange to me as well, for a host of reasons. The MSN article linked above gives one of the most important: when particles spring into existence from energy, they must always be paired with their antiparticles. In other words, matter can, indeed, arise from the energy of empty space, but an equal amount of antimatter must be formed as well.