North American monarch butterflies perform an incredible migration from their summer breeding grounds to a place where they spend the winter. Most of the monarchs that are born east of the Rocky Mountains travel to Mexico, while those born west of the Rocky Mountains fly to the California Coast. Last year, the headlines about those that travel to California were dire:

Probably the most beloved and recognized butterfly in the United States, the western monarch is essentially on the brink of extinction, said Katy Prudic, co-author of a new report from the University of Arizona that found that the monarchs, along with about 450 butterfly species in the Western United States, have decreased overall in population by 1.6% per year in the past four decades.

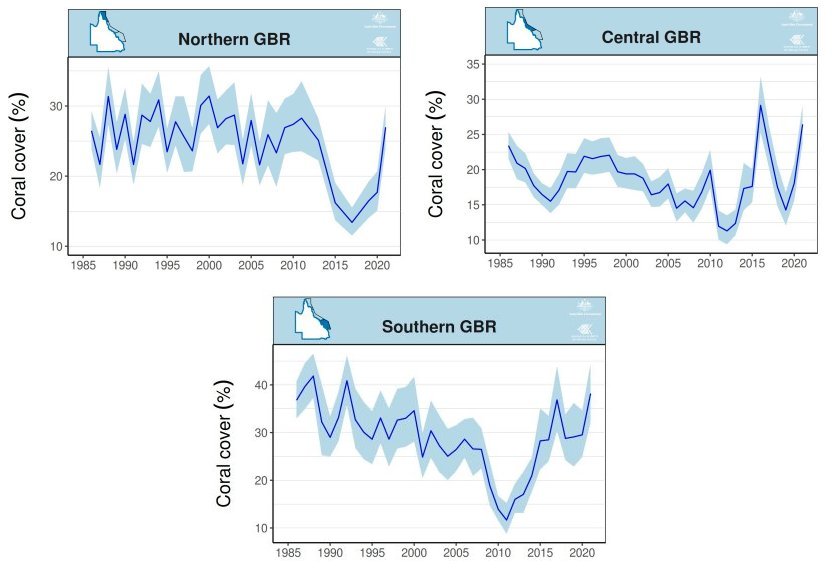

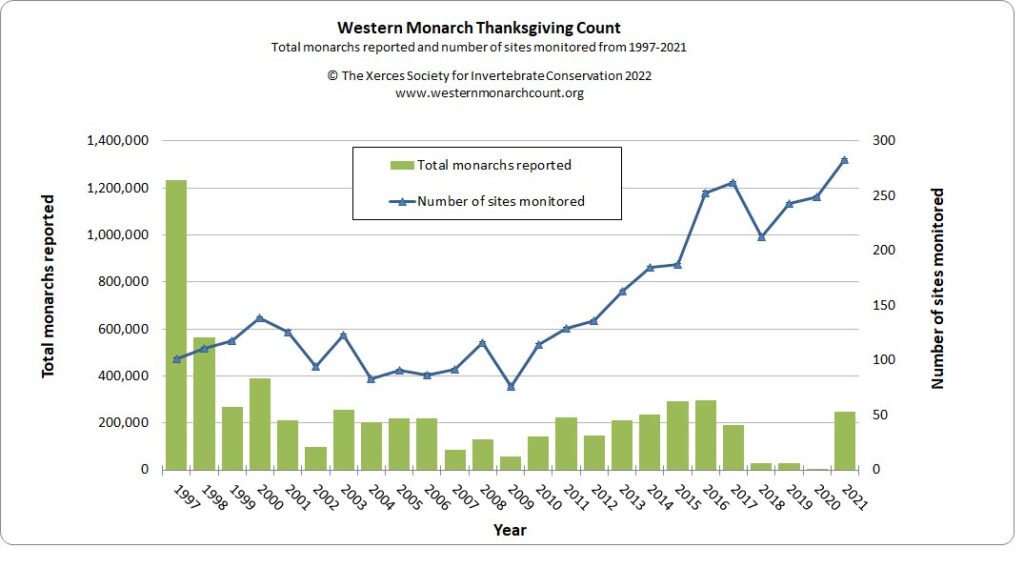

Like much of what you read in science news, that’s just not true. The Xerces Society for invertebrate conservation does detailed surveys of western monarch populations, and here are their results for the “Thanksgiving Count,” which is done over three weeks around Thanksgiving:

Looking at the graph, you can see that Katy Prudic is simply wrong. In fact, the western monarch population has both decreased and increased over the past 24 years. Of course, you can also see why the headlines were dire in 2021. The monarch population is barely visible on the graph in 2020. It was the lowest seen in the entire period. So clearly, western monarchs were on the verge of extinction. However, last year’s count shows a population that is the eighth largest in that same time period!

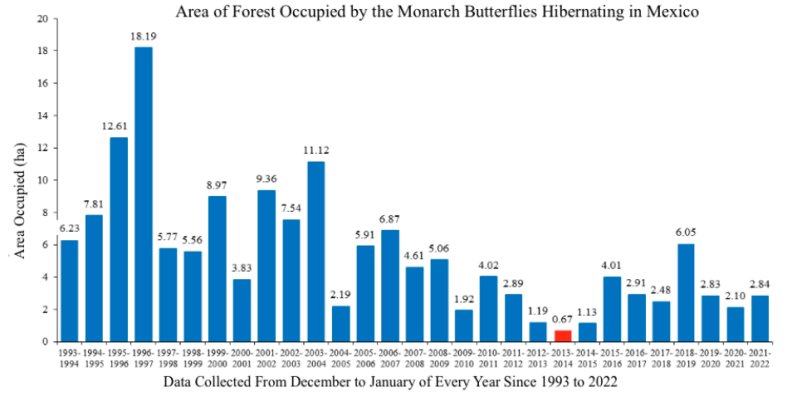

And honestly, anyone who studies these amazing migrations should not be surprised. After all, the population of the monarchs that migrate to Mexico experienced a similar dramatic drop in population back in 2014, but they also recovered from it.

What does this have to do with climate change, aka global warming? First, there have been the predictable attempts to cite it as a cause for the monarchs’ woes. More importantly, however, it shows how dangerous it is to use a trend in nature to make dire predictions.

In both populations, the number of monarchs increased and decreased, but the overall trend for more than 20 years was downward. Then, there was a sudden change, and the decline stopped. This is the way nature works. There is a lot of variation, and tenuous trends in those variations usually don’t mean much.

Now don’t get me wrong. There is a lot of value in collecting data like population counts and global temperatures, and it is important to be concerned about apparent trends. A good scientist, however, should understand that apparent trends are not necessarily actual trends. As a result, good scientists should not make definitive predictions based on them.