In several previous articles (here, here, here, here, and here), I have been highlighting the groundbreaking work of Mark Armitage at the Dinosaur Soft Tissue Research Institute (DSTRI). If you haven’t heard about the amazing work he has been doing, you should read every link given above. If you have been following Armitage’s cutting-edge original research, then you will be pleased to learn that he has published yet another article with yet another first in the field of paleontology.

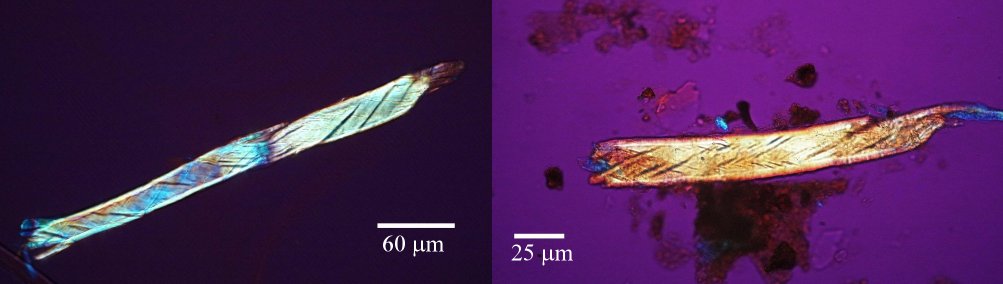

The article is entitled, “First Report of Peripheral Nerves in Bone from Triceratops horridus Occipital Condyle,” and even if you get lost in the terminology, the pictures are well worth perusing. Essentially, Armitage does a microscopic analysis of nerves from a chicken (like the one pictured on the left above) and compares them to nerves that were isolated from the condyle (the rounded end of a horn) of a Triceratops fossil (like the one pictured in the right above). He shows that the structures from the fossil have all the physical characteristics of the chicken nerves, which indicates that they really are nerves from a vertebrate animal. That means they are not contaminants. They came from the dinosaur.

Look, for example, at the pictures above. The white bars tell you the scale in micrometers (millionths of a meter). Notice the pattern of dark lines wrapping around the chicken nerve on the left. That is characteristic of a sheath that wraps around the bundle of fibers which makes up the nerve. As you can see, the same pattern appears in the structure that was isolated from the Triceratops fossil, which is shown on the right. Two even more stunning photographs appear on page 5 of the article. In Figures 12 and 13, you can actually see deatils of the sheaths themselves. They are extremely thin and delicate, and yet they were found in a bone that is supposed to be 65 million years old!

It is important to note that these aren’t stiff, petrified structures. Armitage removed the minerals that had preserved the bone (he “decalcified” it), leaving soft tissues behind. As he says in the article:

The flexibility of individual decalcified nerves was astonishing. Nerves held at each end with fine needle forceps only broke into two pieces after repeated tugging. An example of the flexibility of these nerves is seen in Figure 15 where the fascicle rotates through a gentle, unbroken loop and descends into other curvatures before terminating to a point.

Those who are forced by their preconceptions to believe that dinosaur fossils are millions of years old are still scrambling to find any way in which delicate, soft tissues can avoid decomposition for millions of years. The original discoverer of soft tissue in dinosaur bones, Dr. Mary Schweitzer, published an attempted explanation a while ago, but Armitage himself has shown that it isn’t consistent with the data. Chemists have also shown that the explanation isn’t consistent with what we know about chemistry.

Those who are forced to believe in an ancient earth will, no doubt, come up with more special pleading to try to explain how soft tissue can avoid decomposition for millions of years. But for those who are willing to actually follow the data, it is clear that the most reasonable explanation is that the bones are not millions of years old.