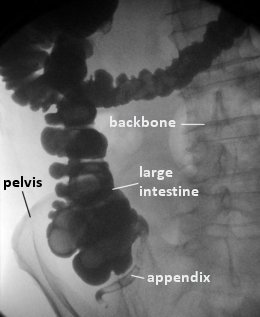

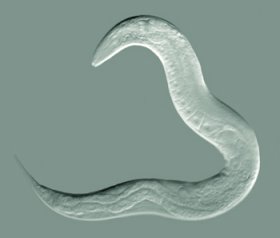

Before that happened, however, Christopher Cherniak did a detailed analysis of the creature’s nervous system. Approximately one-third of the cells in the roundworm’s body are nerve cells, so the nervous system is obviously important to this tiny animal. The system is made of clumps of nerve cells (called ganglia) in the head, tail, and scattered throughout the main nerve cord, which runs along the bottom of the worm’s body. While this system is “simple” compared to the kind of nervous systems you find in many other animals, it has served as a model for helping scientists understand how nervous systems develop and function in general.

Of course, since the nervous system has to process sensory information and control various muscle movements, the ganglia must be connected to one another, to the receptors that sense the outside world, and to the muscles that the nervous system controls. Obviously, then, there is a lot of “wiring” involved. Cherniak wanted to know what determined how this wiring was done in the animal, so he computed all the possible ways that the worm’s nervous system could be wired, given its structure and the number of components it had. His computation indicated that there were 39,916,800 ways the wiring could have been done.

Now that’s a lot of possibilities, but even back in 1994, computers could easily analyze all of them, so he used 11 microcomputers to analyze all 39,916,800 ways the nervous system could be wired. It took them a total of 50 hours to churn through the analysis, but what they found was incredible!

Continue reading “Nematode Nervous System: A 1-in-40-Million Design”