But wait a minute. Haven’t experiments shown that apes can communicate in a very sophisticated way? If you read too much of the popular press, you might think that’s true. However, consider the words of Dr. Jonathan Marks, Professor of Anthropology at UNC-Charlotte and an expert on communication in apes:2

For all the interest generated by the sign-language experiments with apes, three things are clear. First they do have the capacity to manipulate a symbol system given to them by humans, and to communicate with it. Second, unfortunately, they have nothing to say. And third, they do not use any such system in the wild…There is in fact very little overlap between chimpanzee and human communication. (emphasis mine)

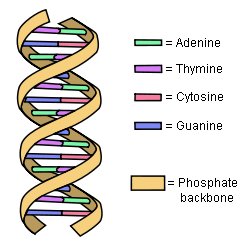

So what is it that produces the remarkable difference between apes and humans when it comes to communication? Evolutionists thought they might have at least a partial answer to this question. If you look in detail at human genes and chimpanzee genes, you see some remarkable differences among those genes that deal with hearing. As a result, it has been widely suggested that the human lineage experienced “accelerated” evolution in its hearing genes, which in turn produced our ability to utilize language, which in turn produced our ability to communicate in a sophisticated way.

Not surprisingly, additional data have falsified this evolution-inspired notion.

Continue reading “The Gorilla Genome Falsifies Another Evolution-Inspired Idea”