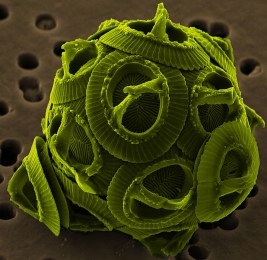

(click for credit)

The picture shown above is of an ocean-dwelling microscopic organism known as a coccolithophore. It makes its own food via photosynthesis, and it also makes the “plates” that you see covering it. It makes them by absorbing bicarbonate (HCO3–) and calcium from ocean and making calcium carbonate (CaCO3). When coccolithophores die, their calcium carbonate plates sink to the bottom of the ocean, making deposits of chalk.

Now it turns out that this process of making plates out of calcium carbonate is influenced by the acidity of the water. The more acidic the water, the harder it is for coccolithophores (and all organisms that do the same chemistry) to make calcium carbonate. Well, increasing levels of carbon dioxide leads to increasing acidity (technically, lowering alkalinity) of ocean water, since carbon dioxide can react with water to form carbonic acid. It is therefore assumed that rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere will harm coccolithophores. As one book on biodiversity puts it:1

Higher atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, by making oceans more acidic, could reduce coccolithophore populations (by interfering with their skeletal formation), thereby reducing a major CO2 sink and leading to still higher levels of atmospheric CO2 concentrations.

Fortunately, actual scientific observations demonstrate precisely the opposite.

Continue reading “Yet Another Global Warming Alarmist Prediction Has Been Falsified”