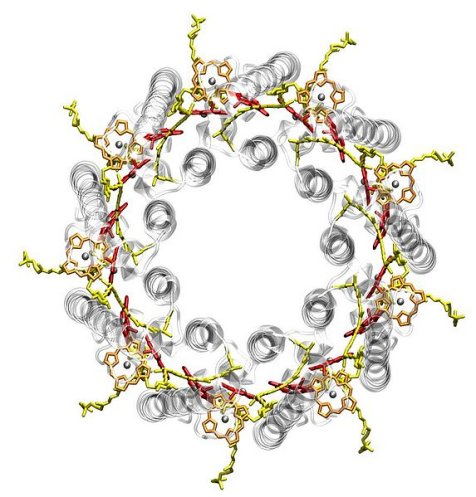

Many aspects of nature are a mystery to science, and at least part of the reason is that nature has been designed so incredibly well. There are systems running in nature that are simply too complex for us to understand and, as a result, their functions remain a mystery. Not all that long ago, for example, many biologists were silly enough to actually think the human genome was mostly junk, simply because they couldn’t understand what the vast majority of the human genome does. Of course, as we have learned more about DNA, we have learned that what was once considered “junk” is vitally important (see here, here, and here, for example). Since the Encode project published its first major results, most reasonable biologists have slowly started to realize what creationists have said all along – there really isn’t much (if any) junk DNA.

Even on a larger scale, there are many aspects of nature that are very hard to understand. A recent article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America provides an example:1

Animals often produce substantial forces in directions that do not directly contribute to movement. For example, running and flying insects produce side-to-side forces as they travel forward. These forces generally “cancel out,” and so their role remains a mystery.

Why would a moving animal expend energy to produce forces that are perpendicular to its motion? Those forces don’t contribute to the animal’s forward motion, and they tend to cancel each other out. As a result, they are often called “antagonistic forces.” Such forces seem like an utter waste of energy. Nevertheless, lots of animals do this. In addition, some animals exert antagonistic forces even when they are not moving in a given direction. Hummingbirds, for example, produce antagonistic forces when they are hovering over a flower.

To understand the purpose of antagonistic forces, the authors of the study examined the glass knifefish (Eigenmannia virescens). When this fish is “hovering” in the water, it uses its fins to produce antagonistic forces. It has been thought that these forces might improve the fish’s ability to control its position and orientation in the water, but no one understood how.2