Not too long ago, a reader sent me an email that said:

I just found out about CRISPR and Cas9. From what I have learned about them they are very powerful and will lead to great things (good and terrible alike).

I was wondering if you could write a blog article on them when you get a chance. I would love to hear your perspective.

The reader is exactly right. CRISPR and Cas9 team up to make a powerful gene-editing tool that has incredible potential. While much of that potential is positive, some of it is quite negative.

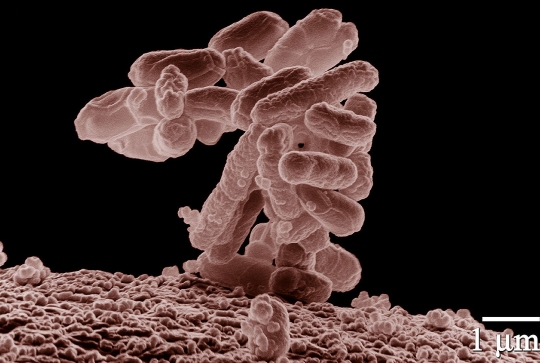

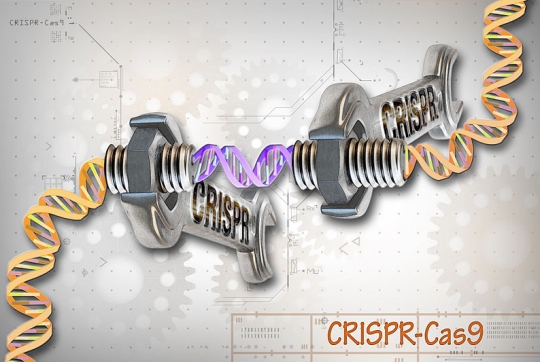

To best understand the good and the bad of CRISPR and Cas9, you need to know what they are and what they can do together. CRISPR stands for “clustered regular interspaced short palindromic repeats.” Originally discovered in bacteria, it is a strand of RNA that is hooked to a CRISPR-associated protein, called a “Cas.” Cas9 is just one possible protein that can be associated with CRISPR, but it is the one that is most commonly used.

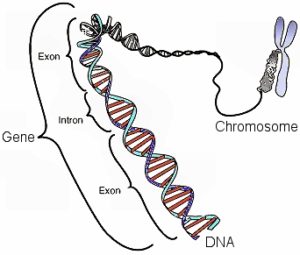

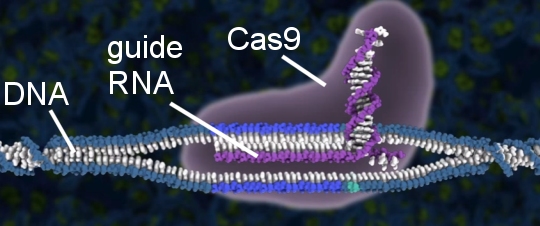

If your eyes are already glazing over, stick with me, because it’s important to understand how this works. RNA is a molecule that links to DNA. A specific RNA molecule targets a specific sequence of DNA. So, if you construct an RNA molecule correctly, it can search an entire DNA molecule, looking for a specific DNA sequence. It can then attach itself to that sequence. That’s what the RNA strand on CRISPR does. It is sometimes called “guide RNA,” because it guides the Cas9 protein to a specific part of an organism’s DNA. Consider the following illustration:

(taken from the video posted at the end of this article)

In the illustration, the guide RNA has found the DNA sequence that it was made to target. Since Cas9 is attached to the guide RNA, it is now positioned at a specific place in the DNA molecule.

Continue reading “CRISPR – A Gene-Editing Technology with Promise and Peril”