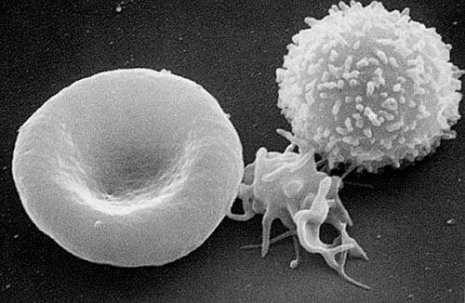

(Click Image for credit)

Of course, the best way to prevent infectious disease is to prevent the infection to begin with. We try to do that with good sanitary practices, but they can only go so far. Regardless of how well we clean our surroundings, pathogens still manage to infect our bodies. In fact, some research is now indicating that we might be a bit too sanitary for our own good.

Medical historians are convinced that the rise in polio the U.S. experienced in the late 1940s and early 1950s was caused by good sanitary practices. When sanitary practices were rather poor, people were regularly exposed to small amounts of the polio virus, usually when they were babies and therefore had the extra protection given to them by the antibodies they received through their mothers’ milk. Their immune systems were able to conquer the weak exposure to the virus with the help of their mothers’ antibodies, and thus they became immune. As sanitary practices improved, however, fewer people were exposed to small amounts of the virus as infants. As a result, when they were exposed to concentrated amounts of the virus (from a person who already had the disease, for example), they would succumb to the disease.1

Some medical researchers take the lesson from the history of polio a step further. They believe in the hygiene hypothesis, which suggests that if a child grows up in an environment that is too clean, he or she will be more likely to contract a host of diseases later on in life, because the child’s immune system was not challenged enough early in life. While the data are not clear enough to determine whether or not the hygiene hypothesis is reasonable, there are some interesting studies that lend support to it.

So…is there a way to prevent infection of a specific parasite without making our surroundings “too clean” and without injecting something into people? The surprising answer might be, “Yes!”