The Home Educating Family Association is a wonderful organization that provides all sorts of useful resources to homeschoolers. They publish a magazine called (not surprisingly) Home Educating Family. Recently, they asked me to contribute to their first issue of 2013, which focuses on pro-life topics. I ended up writing two pieces for them. The first one is entitled “My Little Girl,” and it discusses our experience of adopting a teenager (who just turned 34!). It was probably the most difficult piece I have ever written, as it brought up all sorts of (mostly wonderful) memories. I had such a hard time finding the words I needed to convey what I felt, and then I had a hard time proofreading the piece because of my tears! The article is not available on the internet, so if you want to read it, you will need to get the print magazine.

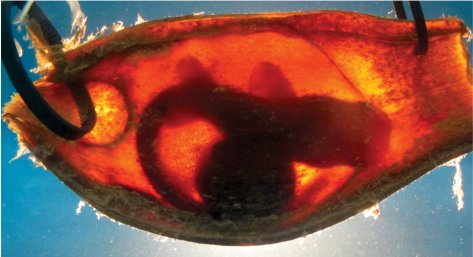

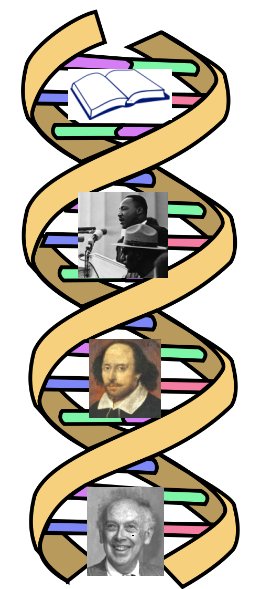

The other article didn’t make it into the print magazine, so it ended up being posted on the Home Educating Family Association blog. It is essentially a composite of two blog posts I wrote previously discussing how a baby in the womb is fully human. It is not emotional, but some might find it interesting. If you care to read the piece, you can find it here.