(click for a larger view)

In a previous post, I compared COVID-19 cases and deaths in Sweden and Denmark. As I said then, it’s because they are very similar countries in the same basic region of the world, but they have remarkably different responses to the disease. Sweden has avoided lockdowns and tried to target their social restrictions, while Denmark has followed the practices of most other countries, strongly limiting what their citizens can do during the pandemic. While no comparison of two different countries is conclusive, I think the results are very interesting. The data come from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, and while it may very well be a biased source of data, at least it is equally biased for both countries.

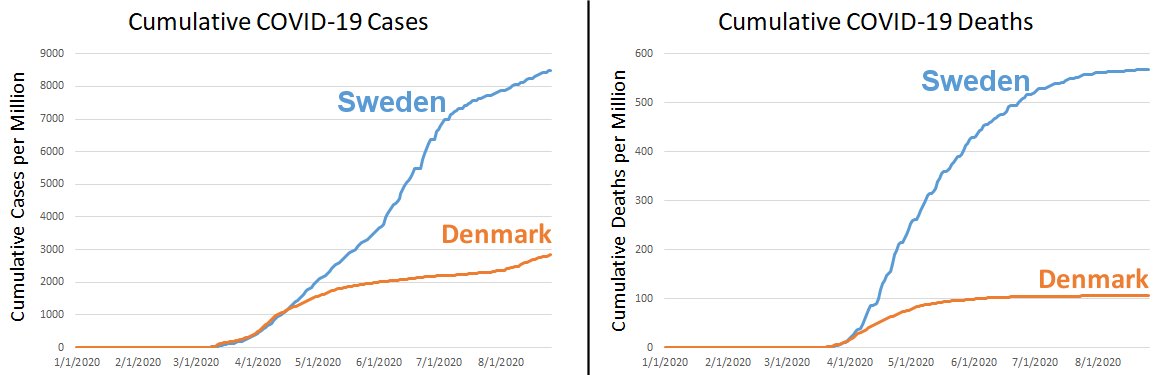

The graph on the left shows the cumulative COVID-19 cases per million. That means each day on the graph shows the total cases that were reported by that date, divided by the population in millions. Initially, Denmark had more cases (probably because initially they were testing more), but as you can see, Sweden quickly surpassed Denmark in cases per million, and the difference between the two countries has continued to grow. Since the death rate of COVID-19 is low (but higher than most infectious respiratory diseases), many people (including myself) think that death rate is a better indicator of the severity of the pandemic. Thus, the graph on the right shows the cumulative deaths per million. Notice that Sweden has more than 5 times the deaths per million as Denmark.

If the comparison between these two countries is legitimate, then, government restrictions did reduce the number of COVID-19 deaths per million in Denmark. However, there are those who suggest that this might be okay, since Sweden will reach herd immunity faster than Denmark. In the long term, then, Sweden will have fewer COVID-19 deaths because the spread of the disease will stop sooner.

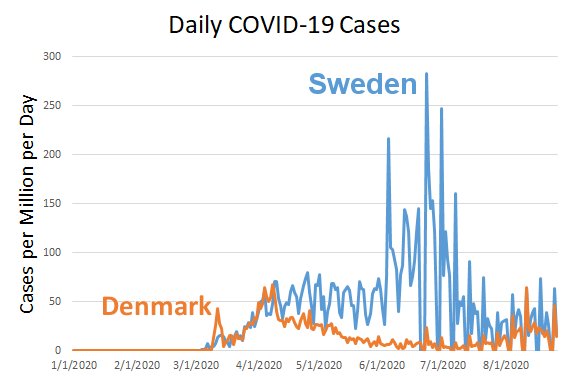

Based on my evaluation of the data, I don’t think Sweden is significantly closer to herd immunity than Denmark. Take a look at the graph below, which records cases per day per million. Rather than adding all the cases reported by a given date (as is done in the graph on the left above), this shows the daily reports of COVID-19 cases per million.

If Sweden were closer to herd immunity than Denmark, the recent cases per million per day in Sweden should be lower than the cases per million per day in Denmark. However, they are not. For most of August, Sweden and Denmark have roughly equivalent cases per million per day. That tells me the disease is spreading roughly the same in the two countries right now, but Sweden has lost five times the people (per capita) as Denmark. As a result, my analysis indicates that Denmark’s restrictions kept a lot of people from dying of COVID-19, and that will continue to be the case in the long run.

Now please understand that this analysis considers only deaths from COVID-19. We know that government restrictions have also caused deaths. There are those who say that the government restrictions will cause more deaths than the ones that were saved from COVID-19. Others say that overall, the restrictions have saved lives. I think the data are insufficient to make that determination, but I do agree that most countries are ignoring the devastating death toll caused by the restrictions themselves. Nevertheless, I think the data are now clear that Sweden’s strategy has not accomplished what the country had hoped it would.

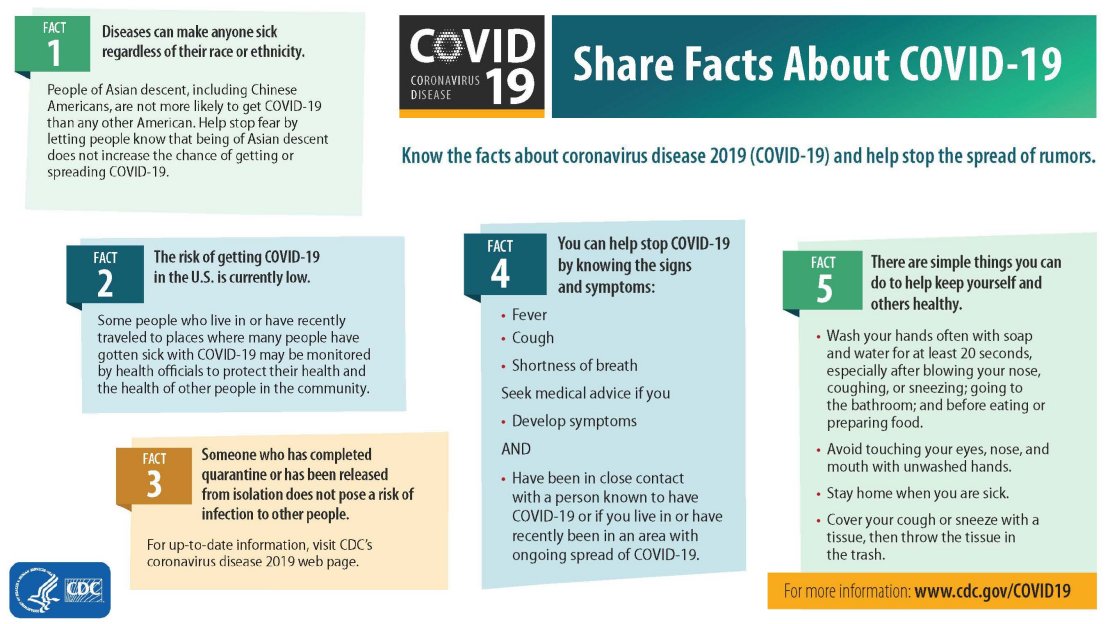

So far, I have written three articles about how horrible social media is as a source of scientific information (see

So far, I have written three articles about how horrible social media is as a source of scientific information (see