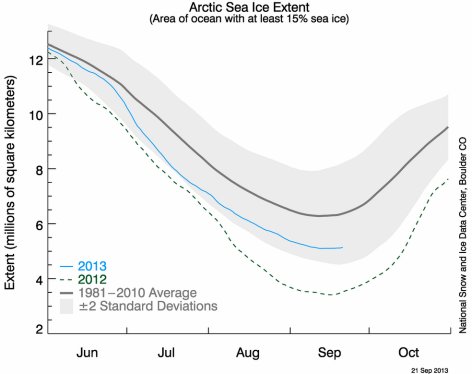

Those who believe that global warming is happening and is caused by people are constantly making predictions about what will happen in the future. Those predictions, however, generally turn out to be incorrect. Not long ago, for example, I showed how miserably the predictions of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change compare to the data, even those that are most friendly to the global warming hypothesis. Well, now that the September equinox has passed, the Northern Hemisphere has officially moved out of summer and is experiencing Autumn. As a result, we can confidently declare that yet another prediction made by global warming advocates has failed.

I doubt that you’ll see this reported in many news outlets, but way back in 2007, Dr. Wieslaw Maslowski, a research professor in the Department of Oceanography at the Naval Postgraduate School, stated that based on his research, the Arctic would be ice-free by the summer of 2013. His prediction was based on a “high-resolution regional model for the Arctic Ocean and sea ice forced with realistic atmospheric data,” and he thought it might be a bit conservative. In fact, he said:

Our projection of 2013 for the removal of ice in summer is not accounting for the last two minima, in 2005 and 2007…So given that fact, you can argue that maybe our projection of 2013 is already too conservative.

Well, as you can see from the graph above, Dr. Maslowski’s “too conservative” prediction has failed miserably. Not only is there ice in the Arctic, there is significantly more ice than there was in 2012. Now, of course, the amount of ice is still way below the average, but it is also way above zero, the prediction that Dr. Maslowski thought might be “already too conservative.”

Continue reading “Yet Another Global Warming Prediction Falsified”