***PLEASE NOTE: This is not a political post, and all political comments will be deleted without mercy.***

***PLEASE NOTE: This is not a political post, and all political comments will be deleted without mercy.***

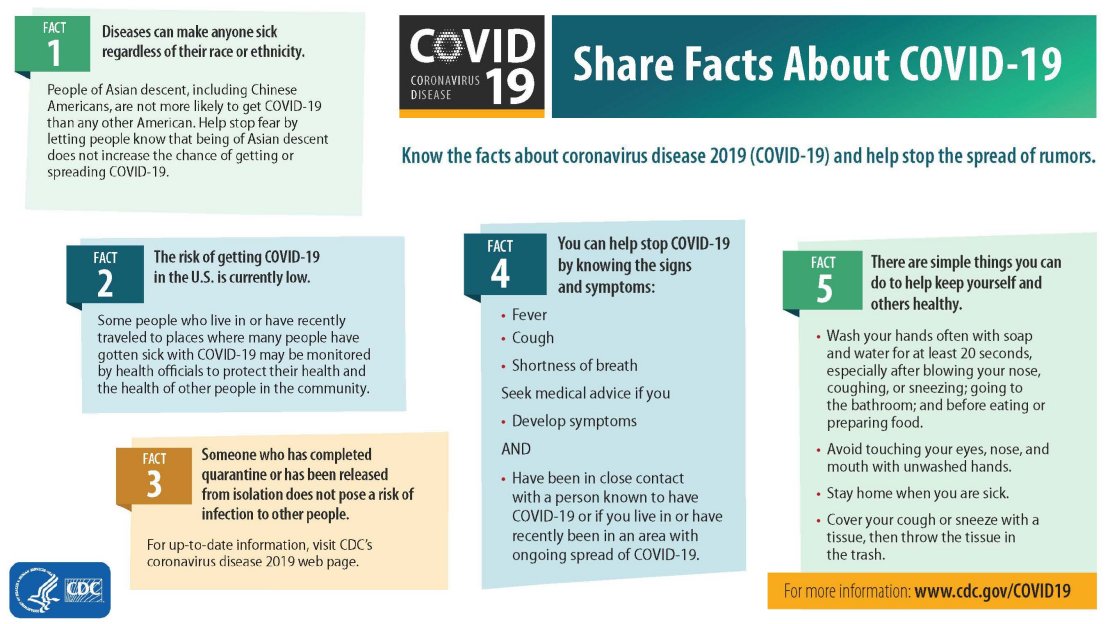

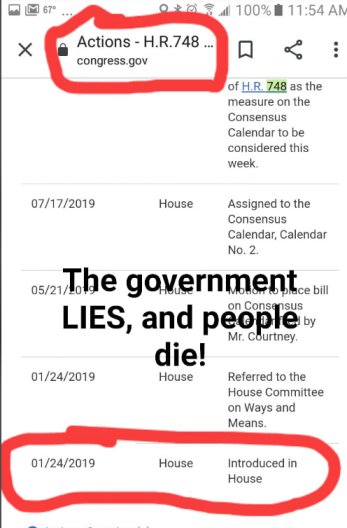

A good friend of mine asked me about something he had seen on Facebook. It wasn’t this particular post, but the message was the same. The image on the left comes from the post I linked. As it shows, the Coronavirus bill that became law on March 27, 2020 (called the CARES ACT) was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives on January 24, 2019. That’s long before we knew about the COVID-19 pandemic. How in the world could this bill be introduced in the House before anyone knew about the virus? As the Facebook post says:

Attention: The conspiracy theorists were right in calling this a “plandemic” and the proof can be found at www.congress.gov. Look up H.R. 748- CARES Act (the Bill that was passed for Coronavirus relief).

To someone uninitiated in the vagaries of legislation in the United States, the fact that the bill was introduced almost a year before anyone heard about the novel Coronavirus does seem to confirm that the entire pandemic was planned. However, like most conspiracy theories, a bit of education is all it takes to understand the real reason behind this odd timeline.

The U.S. Constitution says that all spending bills must originate in the U.S. House of Representatives. Thus, to be Constitutional, any spending bill (including the CARES act) must originate in the House. After it passes the House, it moves on to the Senate for consideration. During that process, the Senate can amend the bill, changing things it doesn’t like. However, once the Senate passes an amended bill, it must go back to the House, and it cannot be sent to the President for his signature until the House concurs with the Senate’s version of the bill.

Because Congress wanted the CARES act to move quickly, it essentially skipped the first step. It did so by taking a bill that had already passed the House and been sent to the Senate. That bill was HR 748, which was originally entitled, “Middle Class Health Benefits Tax Repeal Act of 2019.” Its intent was to repeal a tax that the Affordable Care Act placed on “Cadillac” health insurance plans. It passed the House but was never voted on by the Senate. As a result, it just “sat” in the Senate until March of 2020.

At that point, the pandemic was upon us, and the Senate decided it needed to pass a relief bill fast. It took HR 748, stripped the bill of its content, changed the title, and “amended” it by writing an entirely new bill. The details of the bill were crafted with input from the House leadership so that once it passed the Senate, the House would quickly concur with the “amendment” so that it could be signed by the President, who had also been consulted to ensure that he would sign it right away.

So the strange timeline of the CARES act is the result of a “loophole” that the Senate uses in order to speed up the passage of a spending bill, not because the pandemic had been planned ahead of time. You might wonder if using such a “loophole” is really Constitutional. I personally don’t have enough expertise to figure that one out. I have read legal opinions on both sides of the issue, and they just left me with a headache. However, I can tell you that this is not the first time the Senate has used it. In fact, the Affordable Care Act, which was originally called the “Service Members Home Ownership Tax Act of 2009,” was passed in the same way.